Interested in this kind of news?

Receive them directly in your inbox. Delivered once a week.

The CO2 targets backed by MEPs also require a 20% cut in 2025 – from a baseline of a carmaker’s fleet average emissions in 2021. Crucially the sales target for low and zero-emission vehicles includes penalties, so that carmakers which don’t sell enough cleaner cars will have a CO2 reduction target of up to 5% higher.

The Parliament’s vote is in sharp contrast to the European Commission’s inadequate proposal of a 30% cut in 2030 and no penalties for failing to meet the sales target – a last-minute concession following lobbying by German carmakers.

T&E welcomed the vote as a crucial step towards cleaner air, less imported oil and more jobs. But it warned that the agreed ambition still falls short of what is needed to avoid catastrophic global warming and to meet Europe’s climate commitments under the Paris agreement.

T&E’s clean vehicles manager, Julia Poliscanova, said: ‘Despite an unprecedented lobby effort by the oil and car industries, the European Parliament has voted decisively to require carmakers to make their cars cleaner and sell more electric and hydrogen vehicles. This vote is good news for the climate, for jobs in Europe and for the millions of Europeans who will start to enjoy cleaner air in their cities.’

MEPs also backed the introduction of real-world checks on emissions from cars and vans to stop manufacturers cheating tests. But the parliament said no to the double counting of biofuels and other alternative fuels towards the car CO2 targets as they are already promoted through the recently adopted Renewable Energy Directive. They also rejected the idea of over-rewarding plug-in hybrids, which often emit three times more on the road than in the lab.

Next it’s the turn of EU environment ministers to finalise their position on the proposal when they meet tomorrow (9 October). 19 European countries support a 2030 CO2 reduction target of at least 40%. But following the Parliament vote, Germany, carmakers and trade unions are rumoured to have launched a last ditch effort to weaken the positions of France, Italy, Spain and Poland. If any country switches its position the Germans will be able to block a deal. Assuming Ministers agree to 35 or 40%, trilogue negotiations will follow and a final deal is expected by early 2019, ensuring the law is confirmed before the next European elections.

Julia Poliscanova added: ‘A clear majority of EU governments supports Parliament’s decision to accelerate the transition to clean and electric mobility. Only Germany, Hungary, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Romania and Bulgaria oppose higher ambition. We shouldn’t allow Germany to hold an entire continent to ransom over its failed diesel strategy. Ministers should approve Parliament’s decision next Tuesday.’

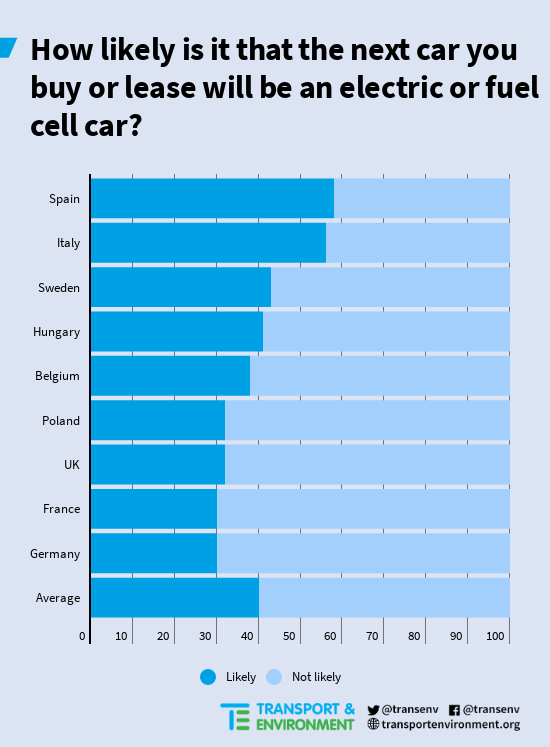

The wants of consumers will be on the lawmakers’ minds following the results of a poll in which 40% said their next car will likely be electric or fuel cell powered. A considerable 5-12% of citizens across the countries surveyed say it is very likely they’ll buy an electric next while a third said it is somewhat likely. T&E said it shows there is an immediate opportunity to grow the 2% of sales that presently can be plugged-in.

Nearly two-thirds (62%) of Europeans surveyed said they think that carmakers are not doing enough to sell electric vehicles by attractive marketing, pricing and offering enough choice. This follows analysis by T&E finding that just 3% of marketing spend is on plug-in cars and a mystery shopping survey has demonstrated dealers are actively discouraging potential buyers. For those citizens who said they would not be likely to buy an electric or hydrogen car next, the biggest barrier is their high price, which was identified by almost two-thirds (65%).

Crucially, when it comes to government action, 60% of Europeans surveyed think that the government should require carmakers to sell electric cars. Over half (55%) want the EU to set ambitious targets that are achievable to reduce CO2 emissions from new cars in 2030.

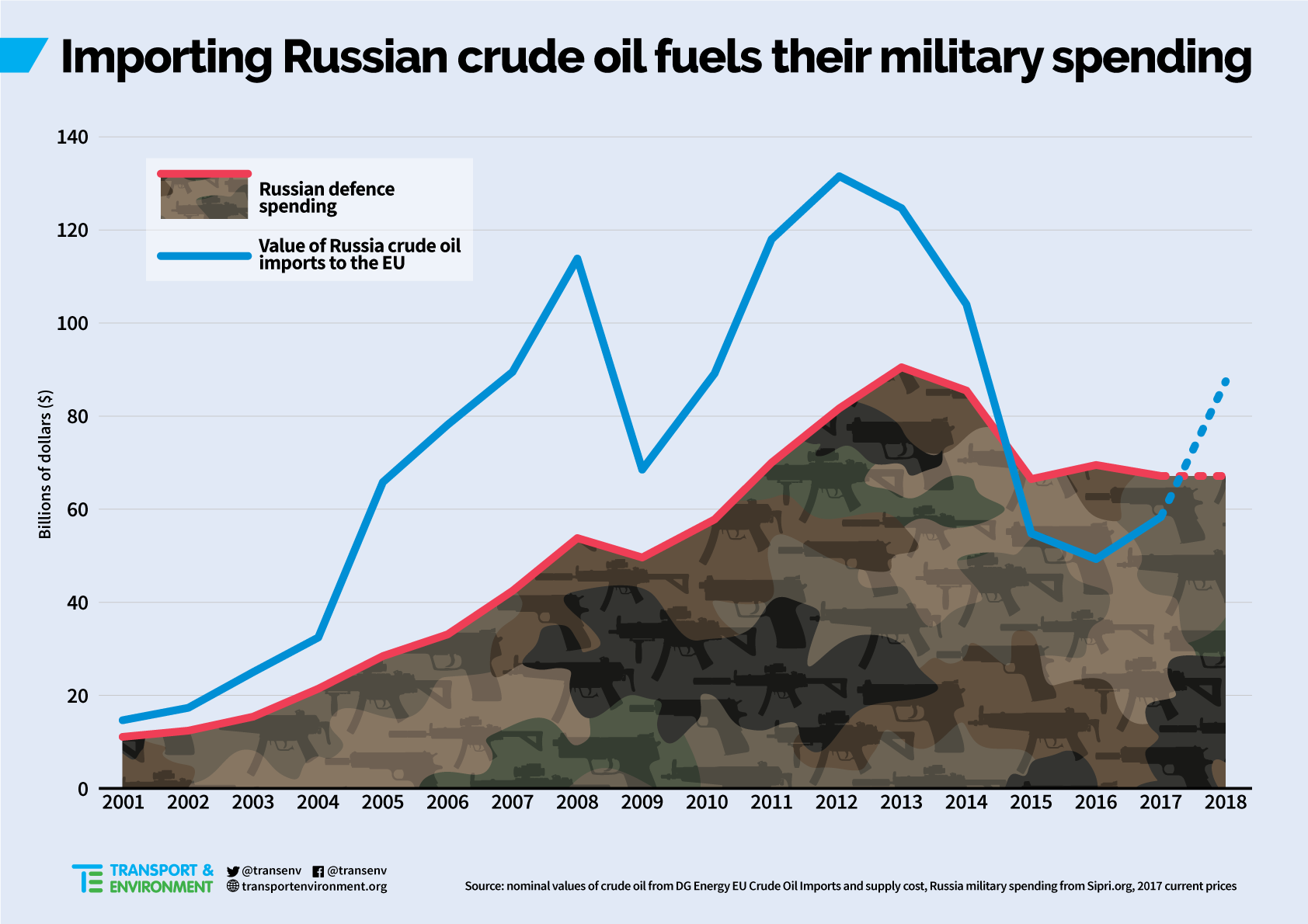

Alleviating Europe’s dependency on foreign oil will also be weighing on ministers. The EU’s rising oil demand has coincided with increases in Russian military expenditure, an analysis published last week shows. Every time a European driver fills their tank, they are sending €7 to Russia, it finds. The EU currently buys around $148 billion (€126bn) of Russian oil a year – enough to fund almost 3,000 new Russian fighter jets or 40,000 new battle tanks.

Around 70% of Russia’s oil production is sold in Europe, while the EU’s transport consumes two-thirds of its oil. Only two of the top 10 oil suppliers to the EU are European (Shell and Statoil); two are Russian; three based are in the Middle East; and two are American. After Russia, a group of Arab OPEC states including Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Libya, Kuwait and Algeria supply roughly a quarter of the EU’s oil – providing the revenues for military expenditure which has contributed to regional instability.

But T&E, which authored the analysis based on Cambridge Econometrics data, said the EU can stop bank-rolling Vladimir Putin’s military by switching to electric and hydrogen cars that rely on renewable electricity produced locally. ‘A shift to electric cars is good for jobs, good for drivers, good for our planet and cuts off the funds to regimes that threaten and try to destabilise our democracy,’ it said. ‘This is in Europe’s strategic interest and we urgently need to develop a long term plan to get off oil. A good place to start would be the Commission’s long-term climate strategy which is due in November.’