Interested in this kind of news?

Receive them directly in your inbox. Delivered once a week.

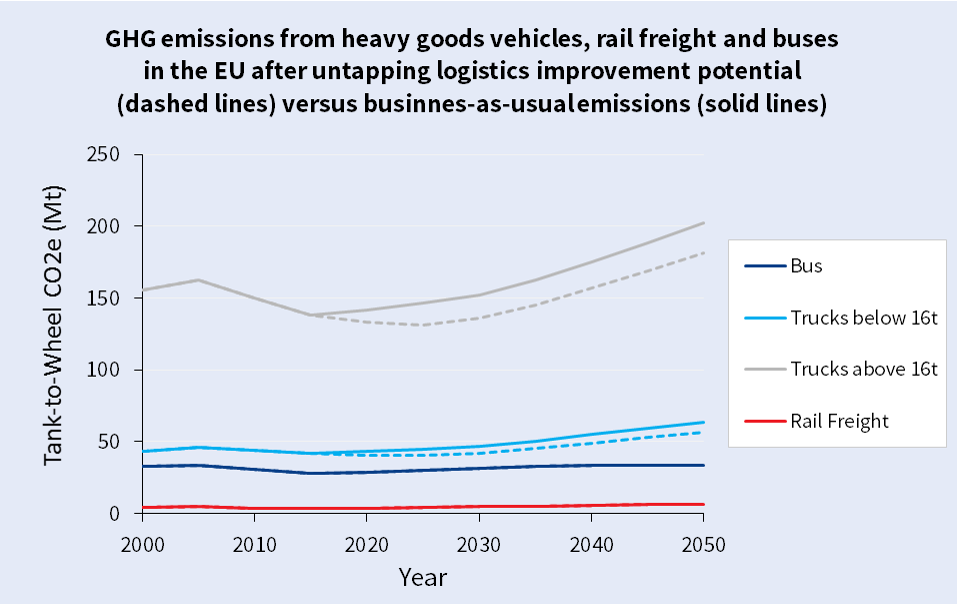

Improved freight transport logistics in the EU could contribute to reduce land freight emissions by 10% by 2050 – compared to a business-as-usual scenario where no improvements take place (see first graph below). To calculate it, T&E used its new European Union Transport Roadmap Model (EUTRM) tool to calculate the contribution of smarter logistics.

The logistics sector is underperforming in Europe. 20% of trucks run empty and, although there is no reliable statistical evidence, partially loaded vehicles are also very common. The inefficient use of trucks leads to too many trucks on European roads and unnecessarily increases the externalities of such vehicles. It can be partially explained by the relatively low costs of road freight transport. Increasing the price of road transport is a way to improve the efficiency of road haulage, the uptake of cleaner vehicles (through CO2 differentiation of road charging), and the attractiveness of cleaner modes.

In the business-as-usual scenario (solid line below), we assumed no improvements in logistics. On the other hand, under the improved logistics scenario, pricing pressure forces companies to be smarter in how and when they use trucks. A truck will operate empty or suboptimally far less often if they’re being charged to do so. This price increase (achievable by means of a toll or through fuel taxation) has no recognisable impact on the economy or trade. Fuel taxes would play a role, but road charging will be used as the tax system to replace lost revenue from a decline in fuel use. As a consequence, we assumed empty trucks would be reduced by one quarter and freight demand would be reduced by 5% from 2030 due to pricing policies. These policies would also help to enable digitalisation of road freight transport, as road is currently too cheap for this technology to be adopted to the extent necessary to have an impact on logistic efficiency.

The European Commission is taking the right steps to unlock the potential described above. They proposed an amendment to the tolling directive (Eurovignette) in May. National governments should introduce, expand and redesign tolls so as to accelerate the market take-up of zero or low-carbon trucks. In parallel, national governments should consider gradually increasing diesel tax, ideally in bigger groupings of countries (to avoid fuel tax tourism). Revenues could be used to fund the transition of the sector.

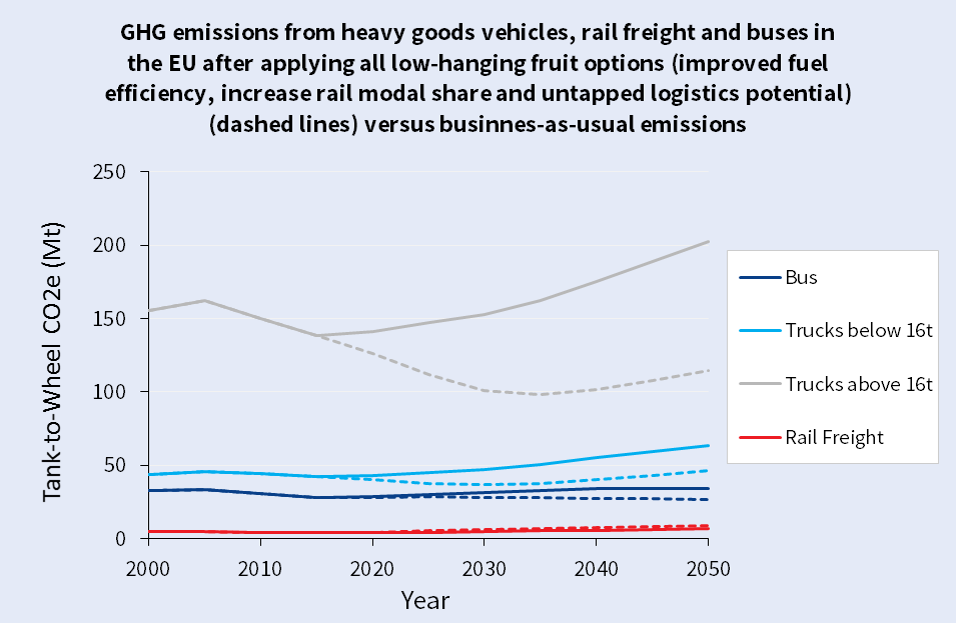

By combining all of what we called the low-hanging fruit measures described in this and previous snippets (improved fuel efficiency and increased rail modal share), significant reductions in GHG emissions can be achieved. The figure below shows the total cumulative effects of these policies. Combined, the above measures could reduce road freight emissions by 36% compared to the business-as-usual scenario, being especially relevant to large trucks above 16 tonnes, where 44% savings are observed compared to the scenario where no policies are implemented.

Although significant progress can be secured, the trajectory shows that the low-hanging fruit measures alone will not achieve full decarbonisation, and by 2035 emissions will begin to rise again due to ever increasing demand. Evidently, new and ambitious policy is required above and beyond currently employable technology to achieve full decarbonisation. In the next snippets we will analyse different options on how that could be done.

For more details, have a look at section 3.1.3 and 3.1.4 of our new study.