Critical metals is the current buzzword around the world. Energy transition at scale and speed is impossible without more of everything from copper to lithium.

China is ahead of Europe. We can have a debate on whether they got there fairly, but we should also recognise our role in letting this happen.

China started building a domestic electric car market and investing in batteries early. The European auto and oil industries were instead pushing first diesel, then plug-in hybrids and now, e-fuels. (The latter do not even exist commercially, and yet risk derailing Europe’s e-mobility transition).

But Europe is still in the game. Our lead in offshore wind, the booming investments in battery factories and a growing electric car fleet (every seventh car sold today is electric) all mean we have the market to attract the critical metals industry, from processing to recycling.

We also have expertise and know-how to develop this industry sustainably. The challenge for Europe is to secure the supply quickly, responsibly and in a way that does not mirror oil’s OPEC.

This is where the European Critical Raw Materials Act comes in. The Commission put forward a draft law in March, and it’s now with the European Parliament and member states to agree. Is it good enough?

The draft act strikes the right balance between the environmental and social safeguards on the one hand, and the need for a quick ramp-up of responsible metals supply on the other. While an EU finance pillar is so far missing (and needed), some adjustments to the text itself can turn this into a strong framework.

Are targets feasible?

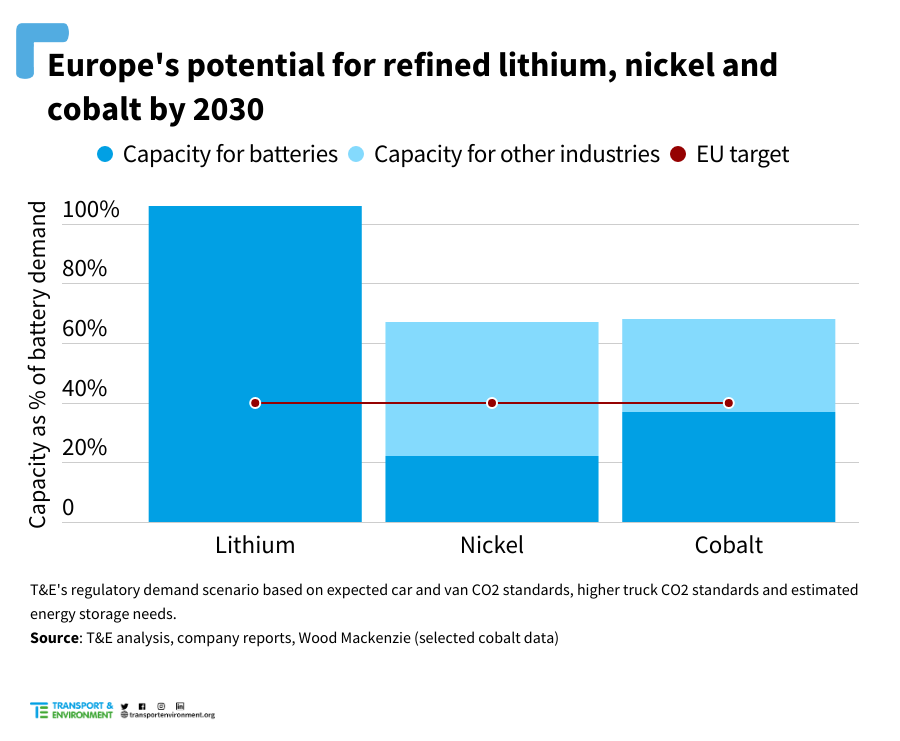

The act aims to onshore some of the metals value chain, notably refining, processing and recycling. T&E’s analysis shows that, with a bit of an industrial push, Europe’s 40% refining goal is feasible.

Europe can refine most of the lithium we will need by 2030. A mature refining capacity in nickel and cobalt already exists, notably in the Nordics, but it will need to be partially adjusted to cater to the batteries market.

On recycling, the potential is there to meet an even higher goal than 15%, but support is needed to make that happen. Today, Europe does a lot of pre-treatment, or shredding and burning batteries into “black mass” that contains all the valuable metals.

But we lack the next step of the value chain: facilities to recover critical metals from that black mass to be used in new batteries. Scaling this material recovery industry in Europe should be prioritized via act’s strategic projects. Europe should also designate battery black mass as waste, which would slow down its exports and give an advantage to local recyclers.

What about safeguards?

While the basics are there, the requirements linked to the selection of strategic projects should be improved. For example, the global convention on the rights of the indigenous peoples should be added to the list. Crucially, only truly robust certification schemes – those with multi-stakeholder governance and independent audits – can be considered, but not as the only compliance check.

Europe should also start understanding the impact of critical minerals extraction better. Various raw materials have different footprints to deal with. For example, most nickel comes from Indonesia, so reducing its carbon footprint is a priority. For lithium, ensuring strict water safeguards is a top issue. The act is vague on when and how those impacts would be addressed, something co-legislators should beef up with deadlines and detail.

Global dimension

Neither recycling nor local production will be there in volumes in the next decade; Europe will have to rely on imports. This means working with resource-rich countries across the world, notably in the Global South.

Competition for resources from Indonesia to Zimbabwe is accelerating. Securing critical metals is the geopolitical quest of the 21st century. Europe should not be naive and strategically consider what it can offer vis-a-vis growing Chinese influence.

This should include helping companies in the Global South move up the value chain to processing, getting our companies to conduct the operations in a clean and fair way, and paying workers a decent wage.

Shorter supply chains, whereby metals are extracted and processed in Africa countries but cathodes and batteries are then produced in Europe, will also cut carbon emissions.

This should not be a colonial-style resource grab. This should be collaboration among equal partners, with Europe sharing its expertise and technology. Europe should also work alongside other big markets, notably the US via the new Raw Materials Club, to create a bigger buyers club based on high and transparent standards.

A strategic and responsible approach abroad and a robust framework back home are needed on critical metals. Supporting this with a focused finance and climate agenda can turn Europe’s green dream into reality.