Interested in this kind of news?

Receive them directly in your inbox. Delivered once a week.

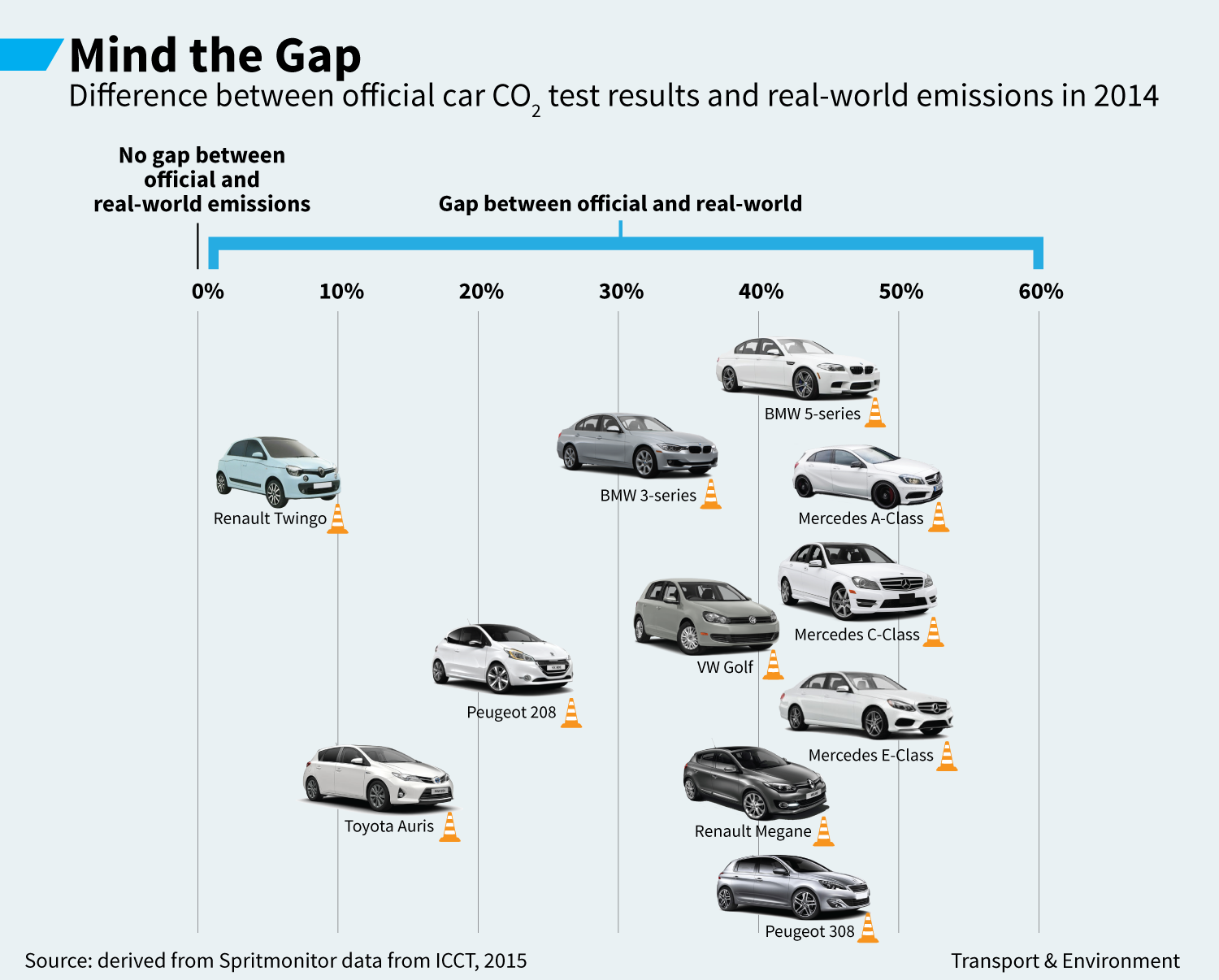

The gap between official test results for CO2 emissions/fuel economy and real-world performance has increased to 40% on average in 2014 from 8% in 2001, according to T&E’s 2015 Mind the Gap report, which analyses on-the-road fuel consumption by motorists and highlights the abuses by carmakers of the current tests and the failure of EU regulators to close loopholes. T&E said the gap has become a chasm and, without action, will likely grow to 50% on average by 2020.

By exploiting loopholes in the test procedure (including known differences between real-world driving and lab simulations) conventional cars can emit up to 40-45% more CO2 emissions on the road than what is measured in the lab. But the average gap between test results and real-world driving is more than 50% for some models. Mercedes cars have an average gap between test and real-world performance of 48% and their new A, C and E class models have a difference of over 50%. The BMW 5 series and Peugeot 308 are just below 50%. The causes of these big deviations have to be clarified as soon as possible.

Greg Archer, clean vehicles manager at T&E, said: “Like the air pollution test, the European system of testing cars to measure fuel economy and CO2 emissions is utterly discredited. The Volkswagen scandal was just the tip of the iceberg and what lies beneath is widespread abuse by carmakers of testing rules enabling cars to swallow more than 50% more fuel than is claimed.”

The distorted laboratory tests are costing a typical motorist €450 a year in additional fuel costs compared to what carmakers’ marketing materials claim, the report finds. But the car manufacturers are continuing to try to delay the introduction of a new test (WLTP) to be introduced in 2017.

Misleading drivers, cheating the law

On average, two-thirds of the claimed gains in CO2 emissions and fuel consumption since 2008 have been delivered through manipulating tests with only 13.3 g/km of real progress on the roads set against 22.2 g/km of ‘hot air’, according to the report. This means that in the last three years there has been no improvement in fuel economy from new vehicles on the road. Only Toyota would have met its 2015 target without exploiting test flexibilities whereas all the other major carmakers have met their legal limits through exploiting test loopholes.

Greg Archer concluded: “This widening gap casts more doubt on how carmakers trick their customers in Europe to produce much better fuel efficiency in tests than can be achieved on the road. The only solution is a comprehensive investigation into both air pollution and fuel economy tests and all car manufacturers to identify whether unfair and illegal practices, like defeat devices, may be in use. There must also be a comprehensive overhaul of the testing system.”

Cars are responsible for 15% of Europe’s total CO2 emissions and are the single largest source of emissions in the transport sector. The EU’s first obligatory rules on carbon emissions require car manufacturers to limit their average car to a maximum of 130 grams of CO2 per km by 2015, and 95g by 2021.