Interested in this kind of news?

Receive them directly in your inbox. Delivered once a week.

The Japanese manufacturer’s cut from 131 grams of CO2 per kilometre to 115g CO2/km in 2014 – by far the largest gain made by any major manufacturer in recent years – is mainly the result of improved efficiency in combustion engines and not the increase in sales of its electric vehicle, the Nissan Leaf. Last year’s upgrade of the Qashqai, its biggest seller, brought a range of new engines which were on average 20g CO2/km more efficient – highlighting the untapped potential of fuel efficiency technology to meet more ambitious CO2 targets.

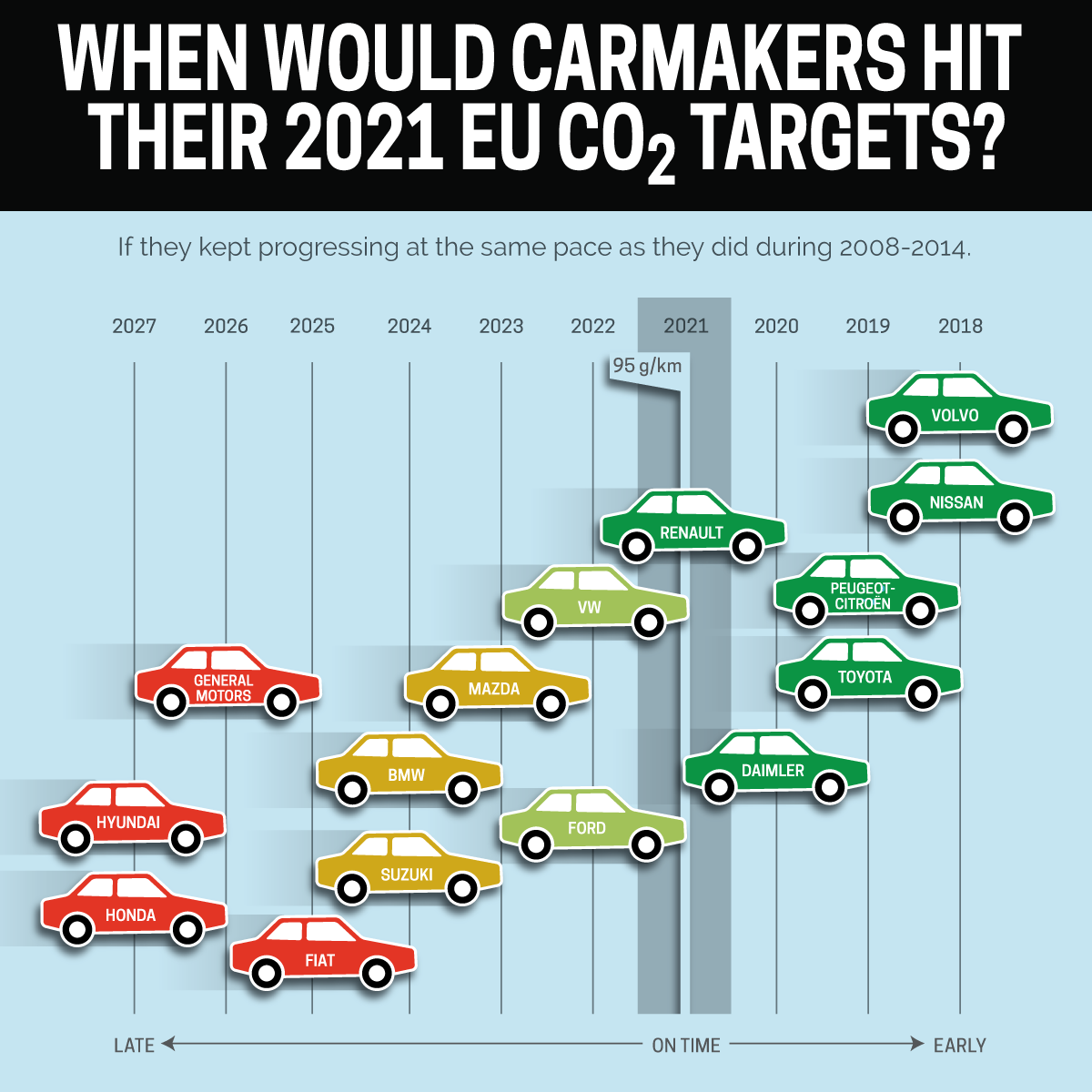

Five carmakers – Peugeot Citroën, Volvo, Toyota, Nissan and Daimler – are ahead of schedule to achieve the 95g/km target by 2021, based on past progress. Renault, Ford and Volkswagen are also broadly on schedule to meet their 2021 target.

Four carmakers – Fiat, GM, Honda and Hyundai – need to significantly accelerate progress to achieve the 2021 target, while the last three have yet to meet their 2015 targets. Overall, the Asian and US companies are making less progress towards their goals than most European-headquartered companies.

Greg Archer, clean vehicles manager at T&E, said: “Regulations to improve car fuel economy are working with carmakers that claim three-quarters of sales in Europe on track to meet their 2021 target. The Commission must now propose a new target for 2025 to maintain momentum.”

While the official figures for CO2 emissions from new cars show a steady reduction, only half this progress – less than 2% improvement per year – is achieved on the road. The gap between official test results and the cars’ performances outside the laboratory, on the road, is considerable and growing. The European Commission plans to introduce a new test cycle – the World Light Duty Test Procedure (WLTP) – in 2017 but carmakers want to delay its introduction until after 2021 and continue using the current flawed 40-year-old test. They are supported by Germany, which wants to reintroduce ways companies cheat the test through the backdoor. [1]

Greg Archer concluded: “Lawmakers should protect motorists from auto manufacturers gaming official tests. We need the new test to be introduced without further delay and end the current abuse of an obsolete system. Ultimately, the new test will provide a more level-playing field for good performers to be rewarded for their good work.”

Cars are responsible for 12% of Europe’s total CO2 emissions and are the single largest source of emissions in the transport sector. The EU’s first obligatory rules on carbon emissions require car manufacturers to limit their average car to a maximum of 130g CO2/km by 2015. This is roughly equivalent to 5.6 litres per 100 kilometres (l/100km) for petrol or 4.9 l/100km for diesel, around 18% below the average in 2007. The target for 2021 is 95g CO2/km (4.1 l/100km for petrol and 3.6 l/100km for diesel) or about a 40% reduction from 2007.