Interested in this kind of news?

Receive them directly in your inbox. Delivered once a week.

Some companies may also need to incentivise customers to opt for lower CO2 variants, such as by selecting a model with a slightly less powerful engine. The cost of the investments required to meet the CO2 standard is estimated to be about half of that incurred by the penalties that would kick in if carmakers fail to comply.

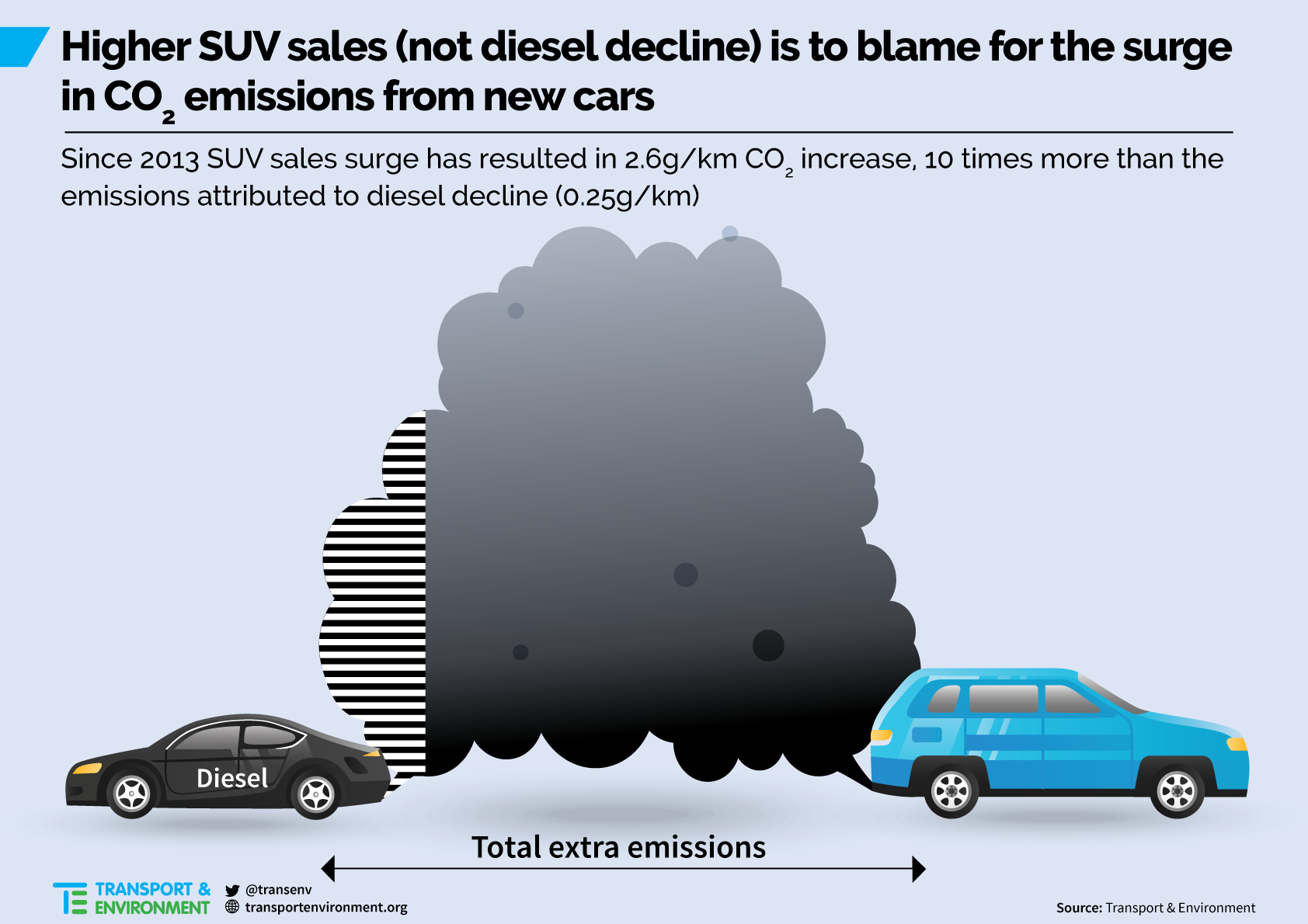

The pitiful progress to date has been caused primarily by three factors. Firstly, a failure to significantly improve the CO2 emissions from conventional engined cars by fitting more clean technologies. Secondly, the very limited supply of zero emission and plug-in hybrid models, purposefully constrained by carmakers to keep selling conventional models. Thirdly, a huge growth in sales of SUVs that have leapt from 7% in 2009 to 36% in 2018 and are expected to reach nearly 40% by 2021.

On average, SUVs have CO2 emissions 16 g/km (or 14%) higher than an equivalent hatchback model, and for every 1% shift in the market to more SUVs, the CO2 emissions increase by 0.15 gCO2/km on average. In other words, the increase in SUVs since 2013 has had a CO2 effect 10 times more than the diesel decline. In reality, carmakers’ performance is even more disappointing since half of the emissions reductions since 2008 happened through manipulation of the official laboratory tests.

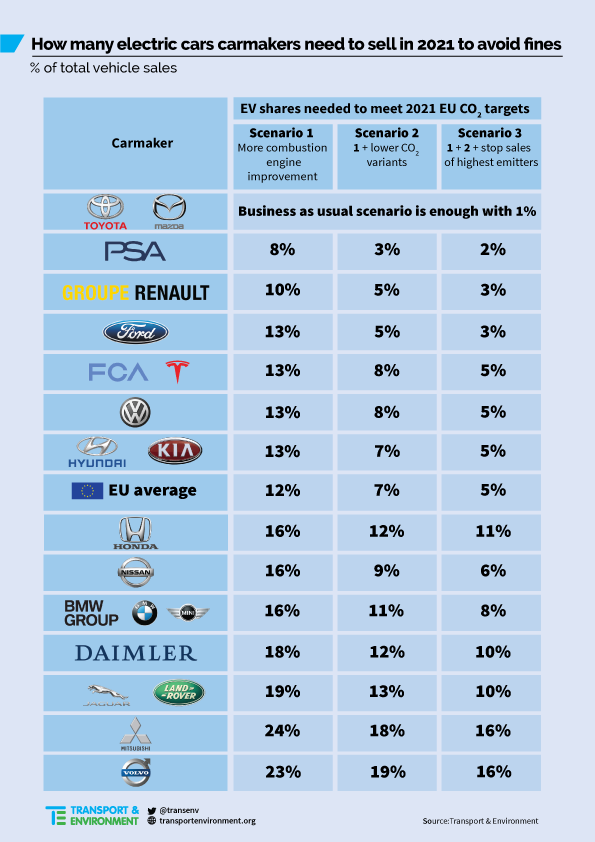

Toyota is best placed to be able to reach its target and has uniquely lowered emissions through increasing deployment of full hybrid technology. The Renault Nissan-Mitsubishi Alliance has the next smallest gap to close in large part due to an early focus on sales of EVs. The companies with the largest gap are: Honda, Hyundai-Kia, Daimler and Volvo, but the latter two are expected to comply shifting a large part of their sales to plug-in-hybrid technology. Fiat-Chrysler also have a large gap but following their pooling with Tesla is comfortably placed to achieve its target. It is clear most carmakers have chosen to pursue short-term profit focused strategy, delaying the necessary investments until the last possible moment.

Compliance plans to meet targets will comprise of four principal elements:

1. increasing sales of zero emission and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (the most future-proof strategy);

2. investing in technology to lower CO2 emissions of conventional vehicles (including mild and full hybrids);

3. pricing, sales and marketing approaches to encourage customers to buy smaller and less powerful engines (with margin implications); and

4. pooling with another company (like FCA with Tesla). The report assesses which combination of measures carmakers will need to adopt in order to meet their targets and is summarised in the figure below.

Overall, the analysis forecasts the EU-wide sales of EVs will go from 2% in 2018 (2.9% in June 2019) to 5% in 2020 (3-7% range) and 10% in 2021 (7-12% range). Around half of sales are expected to be ZEVs and half PHEVs. The jump in EV sales in 2021 results from the EU CO2 target applying to all cars sold in 2021 (not 95%) and because many carmakers will need to make use of most of their super-credit allowance in 2020 already to meet the target.

The range results from the flexible design of the regulation that allows carmakers to do more or less to lower the CO2 emissions of conventional cars (e.g. by shifting sales to lower CO2 variants or limiting sales of highest emitters, such as sports cars and premium SUVs).

The rise in EV sales is significant but new data from IHS Markit anticipates a tripling in the number of EV models available by 2021 and a corresponding large increase in production. To meet targets carmakers will need to ensure the planned production is available on time, or will need to resort to last-resort approaches like ending sales of their highest emitting models that deliver high margins. However, there are good reasons for optimism that the new production in coming years will be sold. Surveys of prospective buyers indicate an immediate untapped market of at least 10%. EV prices will fall with cheaper batteries and large-scale production facilities.

Most governments have implemented tax breaks and grants reducing the higher upfront costs for private buyers, and the total costs of owning an electric car are falling sharply, making this an attractive option for fleets. New charging infrastructure is being installed EU-wide and more charge points are rolled out across main EU motorways and in residential areas. In addition, sales in Norway now count towards the target where 50% of new car sales are now EVs. A large increase in sales and marketing efforts is also changing buyer attitudes with EV advertisement now commonplace in many markets and an array of EV launches planned for this year’s Frankfurt Motor Show.

Some companies will offer whole small city car range as electric, or seek to stock their car sharing fleets with electric cars; others will encourage staff to take EVs as company cars as a means to ensure the necessary sales are achieved. Achieving the required EV sales is a realistic prospect despite the current wide gap to be bridged.

To ensure the regulation achieves its objective and is met there are several actions policy makers should take. Firstly, the car CO2 law is the centrepiece of EU transport emissions policy, it was agreed a decade ago and most carmakers have invested billions in order to comply. The new European Commission should enforce the regulation as intended and not introduce any last- 7 minute weakening under pressure from carmakers or their governments. Secondly, the Commission and Member State testing services and type-approval authorities must ensure there is no manipulation of test results through an extensive process of conformity checking.

Thirdly, governments should assist in the shift to zero and low emissions vehicles by reforming systems of car taxation to increase incentives for zero emission vehicles and raising taxes on high CO2 models. Making high mileage fleets such as taxis and corporate fleets zero emission as soon as possible (as some countries are already doing) will also accelerate EV uptake, as will support for installing charging infrastructure.

The analysis presented in this report shows that although carmakers have fallen far behind the targets, they can and should be met. The 12-year lead time before the target fully applies has unquestionably been wasted by most carmakers except Toyota and Renault-Nissan. Claims that the fall in diesel sales is the cause of rising emissions are false – it is the rise in SUVs, driven by carmakers aggressive marketing of these vehicles that have been the main driver of rising emissions.

If the companies do incur penalties they will only have their own bad decisions and woeful planning to blame, and the penalties will be a necessary reminder they have environmental responsibilities that cannot be ignored.