The sales of battery electric cars in Europe have been growing quickly, with 2 mln cars sold across Europe in 2023 alone. But given China’s edge in battery technology and some feet dragging by European legacy carmakers, more and more of those electric cars are imported from China. The European Commission launched an anti-subsidy investigation into Chinese EVs. With the preliminary ruling expected soon, T&E’s paper is looking at the EV imports into Europe and what an effective response on both EVs and batteries might be.

This paper is part of our work on industrial and trade policy. Europe’s goal should be to decarbonise as fast as possible but to do so in a way that safeguards essential economic, social and security interests. Decarbonisation in the EU should not mean deindustrialisation and trade policy has a key role to play.

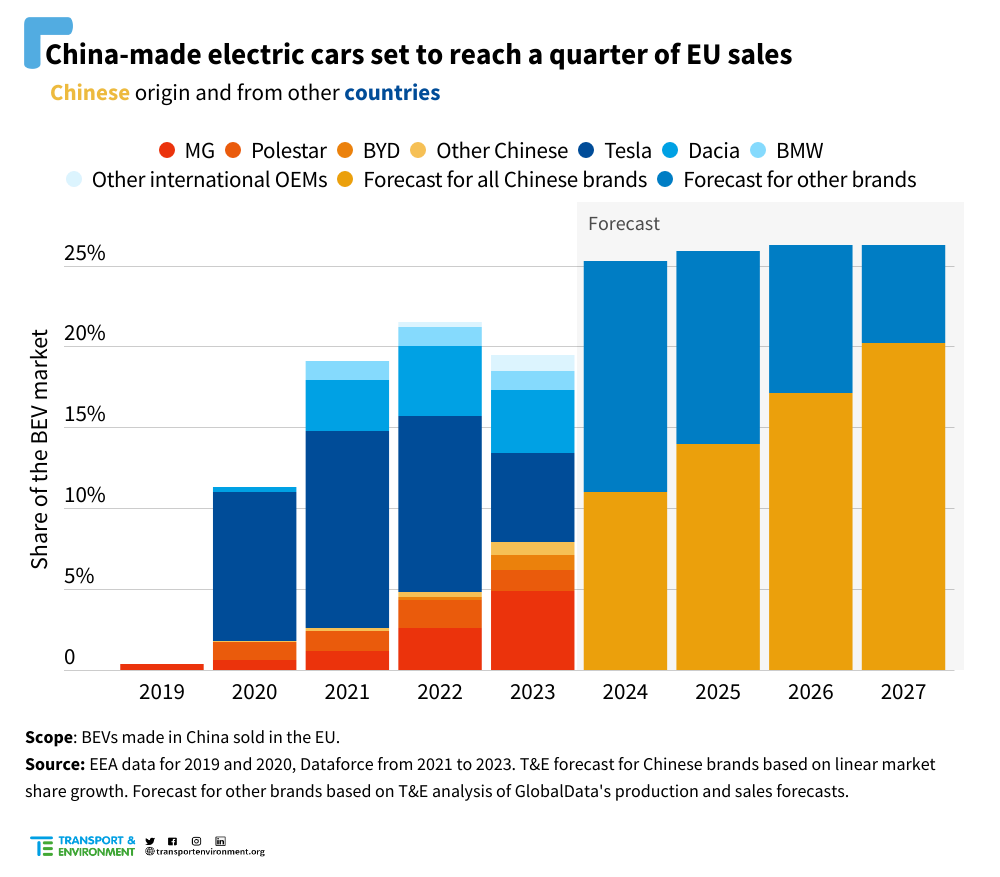

19.5% of all electric cars sold across the EU last year, or 300,000 units, were built in China. In France and Spain close to every third BEV sold in 2023 was made in China. More than half of those come from Western carmakers: 28% of all China made EVs were imported by Tesla, with Renault’s Dacia adding a further 20%. But the Chinese homegrown brands are quickly catching up: from 0.4% of the EV market in 2019 to 7.9% in 2023. T&E projects the likes of BYD, MG and others could reach 20% of the BEV market by 2027.

This shows the challenge Europe is facing. Raising the tariffs to at least 25% (from 10% today) would match the tariff the US originally imposed. Based on the current average vehicle prices, it is expected to make medium cars (both sedans and SUVs) imported from China more expensive than EU equivalents, while compact SUVs and larger cars will remain slightly cheaper. It would also raise between €3-6 bln in additional annual revenue, most of it for the EU general budget that should be reinvested into scaling local clean tech supply chains. The UK should follow suit and adjust upwards its EV import tariffs, while agreeing a European battery alliance with the EU for a tariff-free EV supply chain.

Tariffs will not stop Chinese companies from building factories in Europe as BYD and CATL are already doing. Nor should governments’ aim be to shield legacy carmakers from meaningful competition or lead to a shrinking offer of affordable BEVs for European consumers. The aim should be to localise EV supply chains in Europe while accelerating the EV push, in order to bring the full economic and climate benefits of the transition. It is therefore critical that a higher tariff is accompanied by a regulatory push to ramp up the mass market BEV plans, including in the corporate channel, focusing on sustainable and more affordable offerings.

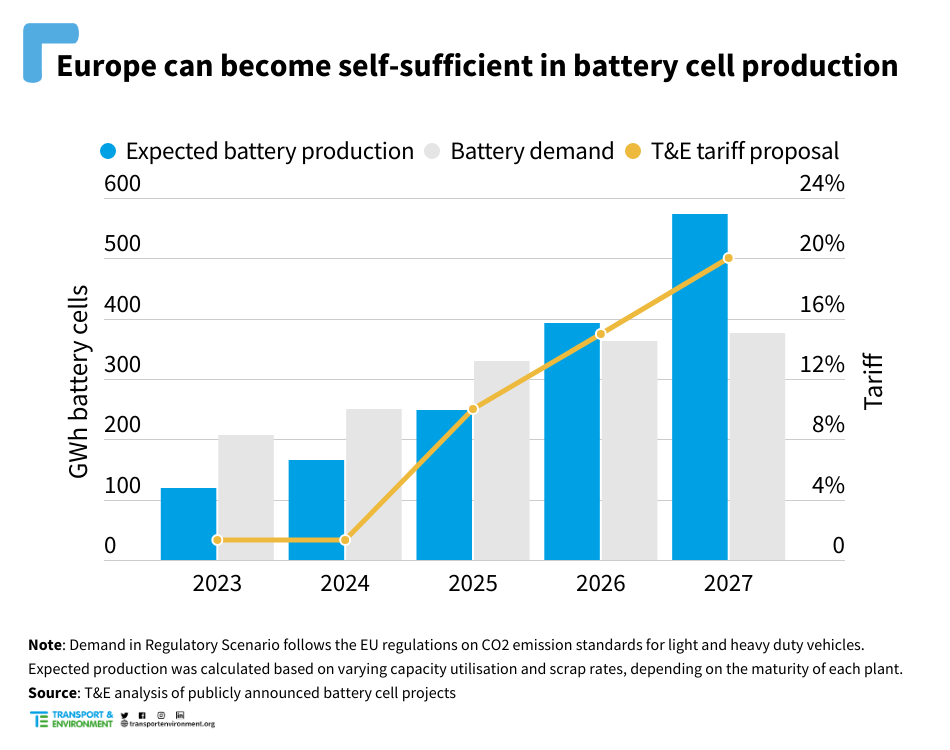

But Europe should not stop at EVs. Trade policy should become an integral part of a more strategic green industrial strategy. Lithium-ion batteries are at the heart of this: more than EUR 180 bln has been invested into the EU battery value chain, predominantly gigafactories, to date. Billions of state aid have been committed to projects such as Northvolt in Germany and Verkor in France. As a result, Europe is expected to supply two-thirds of the demand locally this year and, potentially, could become self-sufficient from 2026 onwards.

But executing this won’t be easy: China manufactures over three-quarters of global capacity with prices at least 20% lower than in Europe (though it is rumoured that Chinese brands get their cells at much higher discounts). Chinese companies are ahead of Europe on technology and supply chain preparedness. The gap with the US is smaller but made-in-America cells benefit from $45/kWh IRA subsidies.

At the same time, the EU battery cell import tariff is the lowest compared to China (10% for EU) or the US (10.9% for China), at a mere 1.3% currently. Without decisive protective and supportive measures, the EU battery industry risks losing out to foreign competition. Therefore, if it is Europe’s goal to have significant battery manufacturing in Europe it will need to introduce measures to create a pull to manufacture locally. Such measures can include:

- Strong battery sustainability requirements that reward local clean and circular manufacturing. But the carbon footprint methodology being currently developed under the new EU Battery Regulation is not sufficient and lacks strict CO2 thresholds.

- Strong “Made in EU” requirements. But the current 40% target in the Net Zero Industry Act lacks teeth.

This leaves tariffs. Higher tariffs can be done in a way that does not cause a trade war. Many Chinese players are already planning battery investments into Europe. Similar to previous trade disputes, an amicable solution can be found. This can include a lower tariff up to a certain volume of imports (e.g. 10-15% of the market) at an agreed minimum price, with the higher tariff kicking in afterwards. To create a pull for local battery cell manufacturing, Europe would need to increase tariffs to at least 20% by 2027 to close the average cost gap with China (likely more, something the investigation should look into). Unlike solar, Europe should act preemptively before it is too late. This should be accompanied by stronger “Made in EU” requirements in public tenders, subsidies and EU grants and loans given to EV and battery makers.

There is a real risk that automotive jobs and know-how will leave the continent as European legacy carmakers have been slow to transition to electric. The aim of Europe’s trade policy going forward should be to secure local manufacturing, ie “made in Europe”, not to shield incumbent companies from competition. Trade protection can give legacy manufacturers some reprieve, but ultimately whether they succeed or fail will depend on their business strategies and ability to compete with new entrants, both Chinese and American. Going faster, not slowing down, is the only way to fend off foreign imports into Europe.

To find out more, download the paper.