Carmakers have been citing low consumer demand for Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs) as the reason behind backpedalling on BEV production plans, placing Europe’s climate targets at risk. But what has been happening in the European BEV market in 2023? And how successful are Europe carmakers at capturing the BEV mass market?

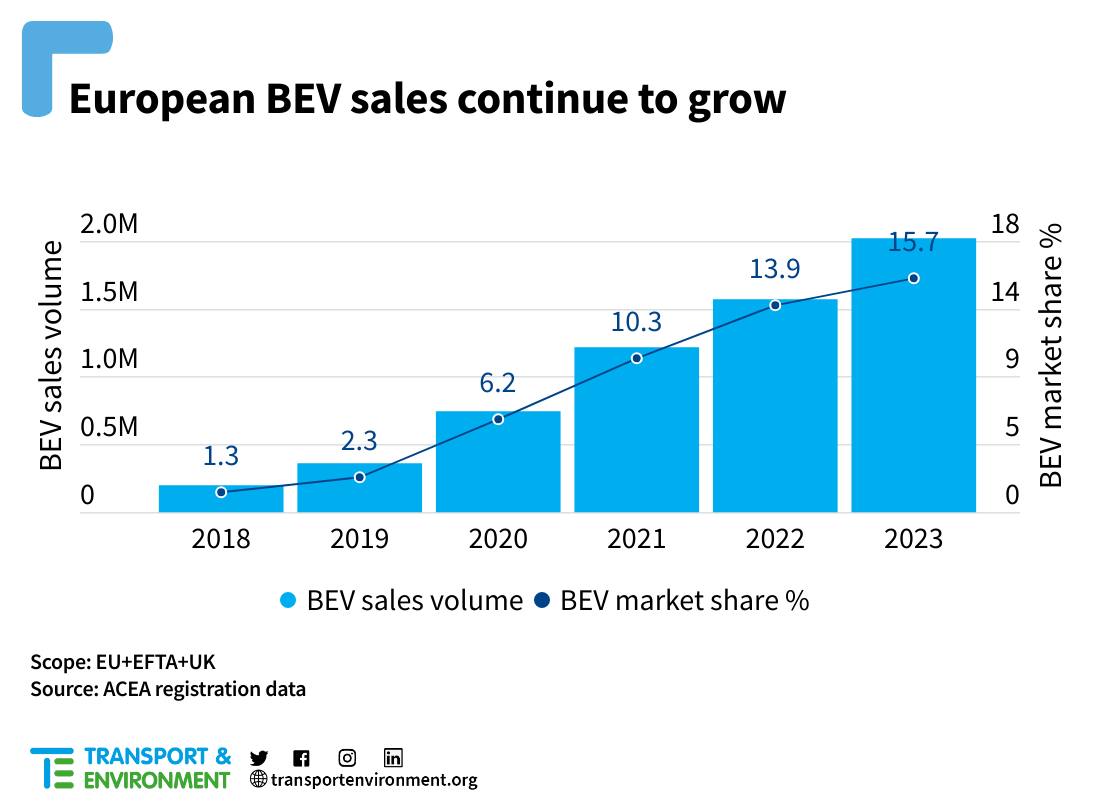

2023 car sales show that, despite economic headwinds, European BEV sales have increased by 28%, and by more than a third in the EU alone. EU BEV sales are now at 1.5 million and BEV market share increased to 14.6% in 2023 vs. 12.1% in 2022. Yet growth has been slower than the rapid BEV uptake driven by the introduction of more stringent car CO2 standards in 2020 and 2021.

When broken down per carmaker, share of BEV sales for some carmakers stagnated (Stellantis, VW) or even decreased (Renault, Ford, JLR). Globally, Europe is falling behind China where BEVs sales and growth are higher; BEVs were 24.7% of China’s car sales in 2023, growing from 21.3% in 2022.

As some western carmakers take their foot off the accelerator when it comes to BEV production, there are serious concerns whether they will deliver the affordable compact models that Europeans want to buy quickly enough to drive forward the mass market uptake of electric cars in 2024.

Carmakers are failing to deliver entry level models at volume

Stagnating car CO2 targets until 2025 have allowed carmakers to prioritise the limited supply of BEVs required by the CO2 regulation on the premium and large segments while failing to deliver affordable, entry level models to the EU market at volume. Since 2018 carmakers have launched just 40 small A and B BEVs compared to 66 of the largest D and E BEVs. Today the impact is particularly evident in the market share divergence of compact B and large D segment cars between the BEV and ICE markets. The compact B segment is responsible for 37% of sales in 2023. Yet for BEVs, it holds less than half of that market share (17%). Instead carmakers have focused on selling larger, more premium D segment BEVs which have more than double the market share (28%) compared to D segment ICE’s (13%). By prioritising new BEV models in the more premium D and E sizes, carmakers are slowing down the BEV mass market to maximise their short-term profits.

The disproportionate focus of carmakers towards larger, more premium models has resulted in high prices for BEVs in Europe. While the average BEV price has fallen in China by over 50% since 2015 thanks to, in part, a greater focus on affordable mass market EVs and supply chain integration, the average European BEV price has increased by €18,000, illustrating how different OEM strategies can lead to very different outcomes for consumers. In China there are 75 BEV models available for less than €20,000, but only one in Europe. The average price in Europe remains high even in the compact segments: €34,000 (A), €37,200 (B) and €48,200 (C). These high prices mean BEVs are not cost competitive for cost conscious European consumers since there are many ICE models available for below €20,000 such as the Citroen C3 or the Seat Fabia.

The focus of European carmakers on SUVs (54% of BEV models launched since 2018), has also impacted affordability since these higher profit vehicles carry a significant price premium compared to non-SUV models in the compact B (+€6,100) and C (+€12,100) segments.

While there have been some announcements by European carmakers that cheaper compact models will be coming in 2024-2027 such as the Renault 5 and VW ID.2. Less than 50,000 cars of the announced cheap models are expected to be produced for Europe in 2024 which is unlikely to satisfy demand. This leaves the European compact, mass market wide open to Chinese competition.

Corporate fleets are failing to lead on BEV sales

Beyond the lack of affordable, compact BEV models, the low BEV uptake in the corporate car segment is also holding back the European BEV market. Corporate cars account for 60% of EU sales and are the perfect candidate for accelerated electrification since corporate cars are already subsidised through tax cuts, companies have the financial muscle to invest in BEVs and generally drive longer distances which means larger CO2 savings when electrified.

However, notwithstanding their privileged position, corporate EU BEV sales are falling behind at 14% vs. 15% in the private segment. This is due to poor national company car taxation policies in many Member States and lack of EU policies that would drive corporate fleet electrification. Only 9 EU countries have company car taxation policies in place which results in a significantly (50%) higher corporate than private BEV share. Yet, if lagging countries reform corporate car taxes, they can accelerate EU BEV sales. If all EU countries had 50% higher corporate BEV sales (than private), the share of BEVs in the corporate segment would have almost doubled (see image below). In short, if the corporate car segment was leading in BEV sales -as it should be because of favourable economics-, then the overall EU BEV market share would have reached 22% in 2023 instead of 15%.

Roll out, not back

Seeing a gap in the European market, many Chinese brands are or plan to sell electric models across the continent, often at more affordable prices. Chinese carmakers may potentially even sell some models at a loss to gain brand recognition and market share. Even if regulations stagnate, incentives are rolled back and the economic climate is not ideal, European carmakers are mistaken if they believe slowing down now will help their competitiveness or survival. Rather than roll back, the fierce competition for the BEV mass market buyer in Europe means it’s time to accelerate, improve technology and keep investing.

Smart EU and national policies are needed to accelerate the affordable mass market. Such policies could deliver 18 million compact and affordable, made in Europe, electric cars by 2030. Specifically the EU should:

- Maintain the 2035 100% zero emission sales target and do not reopen the car CO2 standards in 2026.

- Propose an EU regulation to electrify all new sales of corporate fleet cars by 2030 at the very latest and set earlier targets for big fleets.

- Secure small, affordable EVs for the EU market by supporting social leasing via the EU’s Social Climate Fund and introduce a new EV environmental standard.

- Use EU funds and broader industrial policy tools to support the automotive transition on the condition of providing additional and affordable BEV supply above what is required by the CO2 standards.

- Integrate “Made in EU” and environmental requirements into EV subsidy and other public procurement schemes.

To find out more, download the analysis.

CORRECTION: This briefing was edited on 22 February 2024. The projected production volume of announced affordable models (pg. 12 and fig. 8) was updated to include the Cupra Raval. The launch date of the Renault 5 was also corrected to 2024 in fig. 8.