Interested in this kind of news?

Receive them directly in your inbox. Delivered once a week.

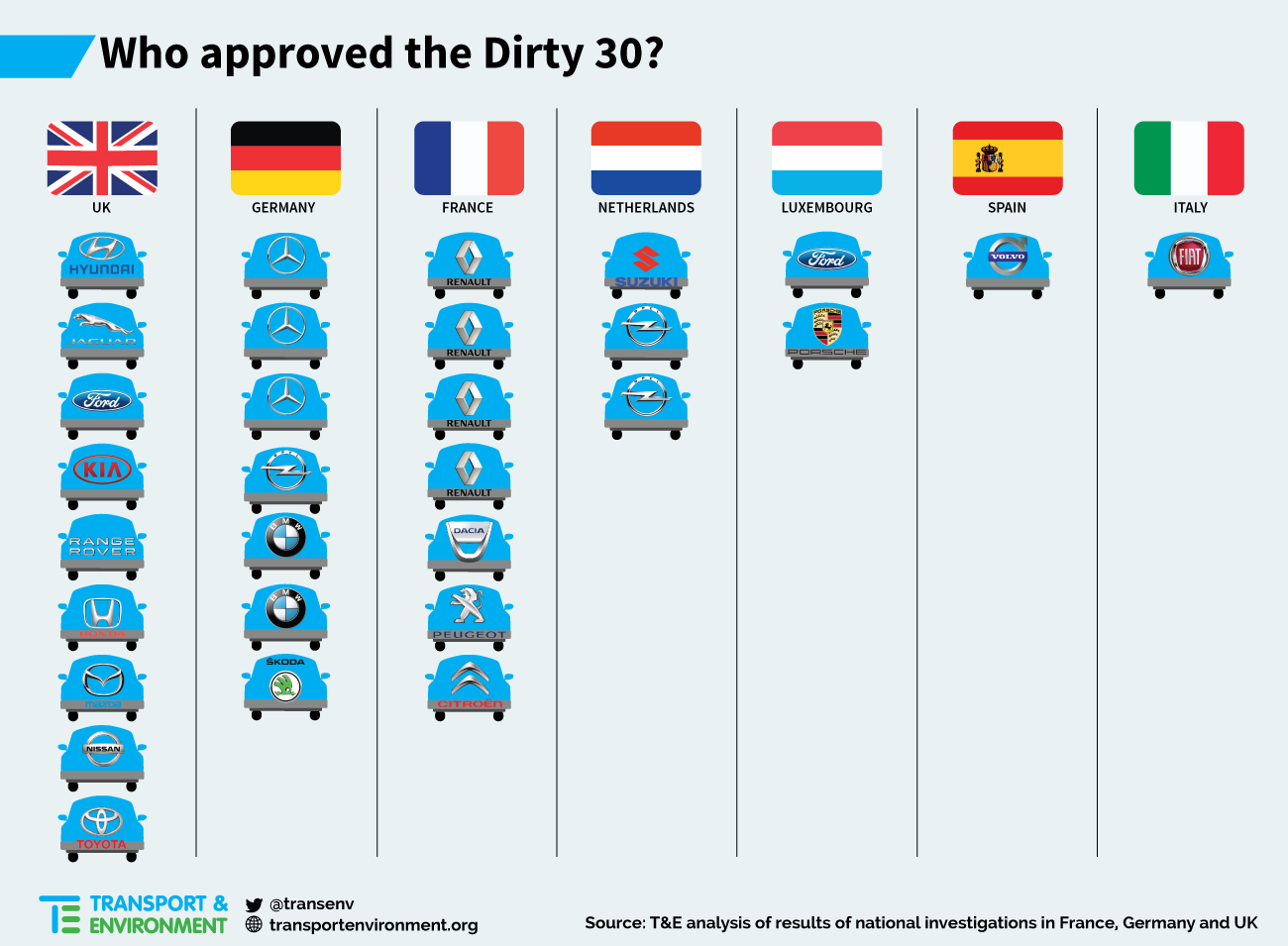

Nine of the ‘Dirty 30’ vehicles were approved for sale by the UK’s VCA type approval authority. These included a Jaguar, a Range Rover, and three British-made Nissan, Toyota and Honda models. Germany’s KBA approved seven car models: three Mercedes, two BMWs, one Opel and one Skoda owned by the VW group. France gave the green light to another seven models – all from French brands: four Renaults, one Peugeot, one Citroën and one Dacia, Renault’s budget marque. Italy rubber-stamped the FIAT 500X, which is reported to be at the centre of a spat between German and Italian authorities over emissions cheating.

Greg Archer, T&E clean vehicles director, said: ‘Carmakers are choosing to play at home with a biased referee, guaranteeing that they win but their cars pollute and people die. What else than Dieselgate do you expect when Germany approved Mercedes, France Renault, the UK Jaguar and Italy Fiat? Either we break the cosy relationship between national authorities and their car brands with effective European supervision and independent testing or the cheating will continue.’

The investigations in France, Germany and the UK found that most cars tested have excess NOx emissions in real life and deploy strategies that turn down or switch off pollution controls in circumstances beyond those prescribed in the EU test, such as lower temperatures, hot engine starts, and rides longer than 20 minutes. The official test begins with a cold start, takes place at temperatures between 20 and 30°C, and lasts 19 minutes and 40 seconds.

T&E said these strategies constituted three new defeat devices, on top of Volkswagen’s, and must be thoroughly investigated so as to force carmakers to come clean on their emission strategies. The mass deactivation of exhaust aftertreatment needs to be stopped by approval authorities and, if necessary, tested in court, it added.

Last week the German government sought to have EU transport ministers blame EU law rather than lax national authorities for Dieselgate. The law was agreed in 2007 by all member states and clearly outlaws defeat devices. Governments only expressed concerns about its ‘vagueness’ after the national investigations laid bare the inadequacy of national approval authorities. National authorities have yet to take legal action against or scrutinise further the many defeat strategies deployed by carmakers.

Last week Industry Commissioner Elżbieta Bieńkowska told ministers that member states had always insisted that enforcement of the EU laws be left up to them, and that this poor national enforcement is behind such high NOx emissions on Europe’s roads.