Interested in this kind of news?

Receive them directly in your inbox. Delivered once a week.

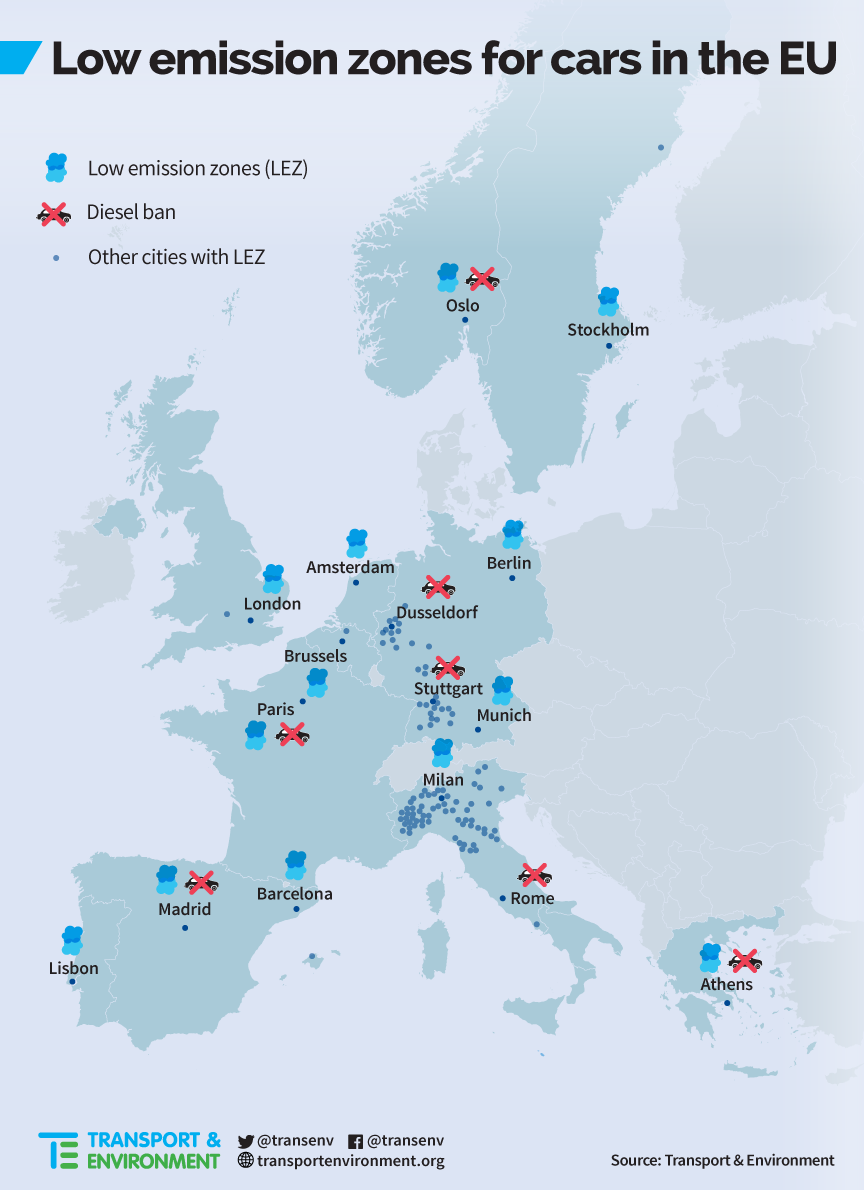

Today there are around 40 million grossly polluting diesel cars and vans on European roads, a legacy of the dieselgate scandal. National vehicle approval authorities remain reluctant to force carmakers to fix these vehicles. If carmakers refuse to clean up dirty diesels, cities that have been in breach of air pollution limits for almost a decade have no other choice but to implement drastic car restriction measures to protect public health. According to the European Environment Agency, diesel cars are the dominant cause of toxic nitrogen dioxide across European cities, resulting in 68,000 premature deaths annually.

Julia Poliscanova, clean vehicles manager with T&E, said: “One of the key weaknesses of the low emission zones and car restrictions in cities is the blanket exemption of mostly dirty Euro 6 diesels. Unless carmakers properly fix these dirty diesels, cities are left with no other option but keep them out of city centres. To be effective, the inclusion/exclusion criteria of these measures should be based on vehicles’ real-world emissions that are now widely available. More importantly, diesel bans should be accompanied by high-quality public transport and infrastructure for shared and zero emission vehicles.”

Two weeks ago, a top German court ruling confirmed that German cities can ban cars and clarified that the right of citizens to breath clean air takes precedence over the right of private car owners to drive polluting vehicles. But national legislation in some countries is preventing cities from taking action, with Copenhagen a key example. The German court ruling should thus be a precedent EU-wide.

Central and Eastern European countries rely heavily on second-hand car exports into their fleets. With many western cities considering outright diesel bans, there is a danger that millions of the grossly polluting vehicles their citizens no longer want will end up on the roads of cities such as Warsaw, Prague and Sofia continuing to bellow toxic fumes in years to come.

Julia Poliscanova concluded: “There’s a high risk that Central and Eastern European cities will be flooded with cheap, dirty diesels that Western Europeans can no longer drive where they want. European Commission should consider what measures can be put in place to ensure all second-hand imported cars have had their exhaust treatment systems fixed or upgraded. All Europeans have an equal right to clean air and a joint European solution is needed.”

The car market in Europe has been skewed in favour of diesel through weak emissions rules and tax breaks. The market grew to 53% of cars sold in 2011 and Europe represents 70% of global diesel car sales. However, since the dieselgate scandal the diesel market share is in steep decline falling by a massive 8% in 2017 to 44%. With additional costs to meet new emissions rules the diesel market share is expected to continue to fall, suggesting costly investments by European carmakers in new diesel engines may prove to be a poor business decision.