Interested in this kind of news?

Receive them directly in your inbox. Delivered once a week.

In fact, shipping’s share of global carbon emissions could rise to 17% by 2050 if no action is taken, scuppering the chances of the Paris agreement preventing dangerous climate breakdown.

To stop this, we’ve got to get scientific. Because greenhouse gases accumulate in the atmosphere, the evidence shows that humanity is left with finite carbon budgets to prevent the world’s temperature rising beyond the dangerous 1.5ºC or 2ºC thresholds, compared to pre-industrial levels.

This carbon budget is 773 billion tonnes for a 1.5ºC world. Exceeding this will lead to the disappearance of the low-lying nations, including South Pacific countries such as the Marshall Islands, Fiji, Micronesia, and Cook Islands. Exceeding the budget of 1,428 billion tonnes for a 2ºC world will cause catastrophic changes to our global ecosystem, the damage from which will be costlier than the entire GDP of many nations.

Exactly how to allocate these carbon budgets fairly to each country and sector is hotly debated. How much of the remaining “pie” is each sector entitled to before it fully switches to zero-carbon technologies?

But using historical emissions data as a guide would mean shipping is entitled to no more than 2.3% of the remaining carbon budget available to humanity to prevent the temperature rising beyond the critical 1.5ºC threshold.

This gives the shipping industry a carbon budget of around only 18 gigatonnes (1 gigatonne = 1,000 million tonnes) starting from 2010 – the baseline year usually used to estimate the total remaining global carbon budget of 33 gigatonnes.

How fast is shipping using up this budget?

According to the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT), international shipping’s annual CO2 emissions reached 812 million tonnes in 2015, while other studies (see UMAS and CE Delft) show annual emissions from shipping will climb up to 1 gigatonne by 2030 if no action is taken. This means that, at its current rate, shipping’s remaining 1.5ºC carbon budget will be exhausted in 12 years.

Before this happens, shipping must be subject to an effective carbon price in the region of $500 tonne/CO2 (€406) in order to make zero emission fuels/technologies cost competitive with current fossil fuels. But the clock is running down: if effective carbon pricing only kicks in by 2030, the industry will have no time left to switch the fleet to zero emission technologies through newbuilds and retrofits. This means the sector has to find fast ways of cutting its footprint now.

According to studies, slowing down ships – known as slow steaming – would greatly reduce their energy use and CO2 emissions due to the cubic relationship between speed and energy use. In plain English this means that if a ship reduces its speed by, for example, 10%, its emissions will come down by around 30%.

If major vessels responsible for half of shipping’s emissions can progressively slow down from 2018, the sector would be able to save at least 1,500 million tonnes of CO2 by 2030 for starters. How would this early slow steaming help the overall transition of the sector?

Firstly, if ships slow steam from 2018, the sector will save a considerable share of the remaining carbon budget in a short time, which will allow it to use this saved budget beyond 2030 for at least another five years – see graph 1:

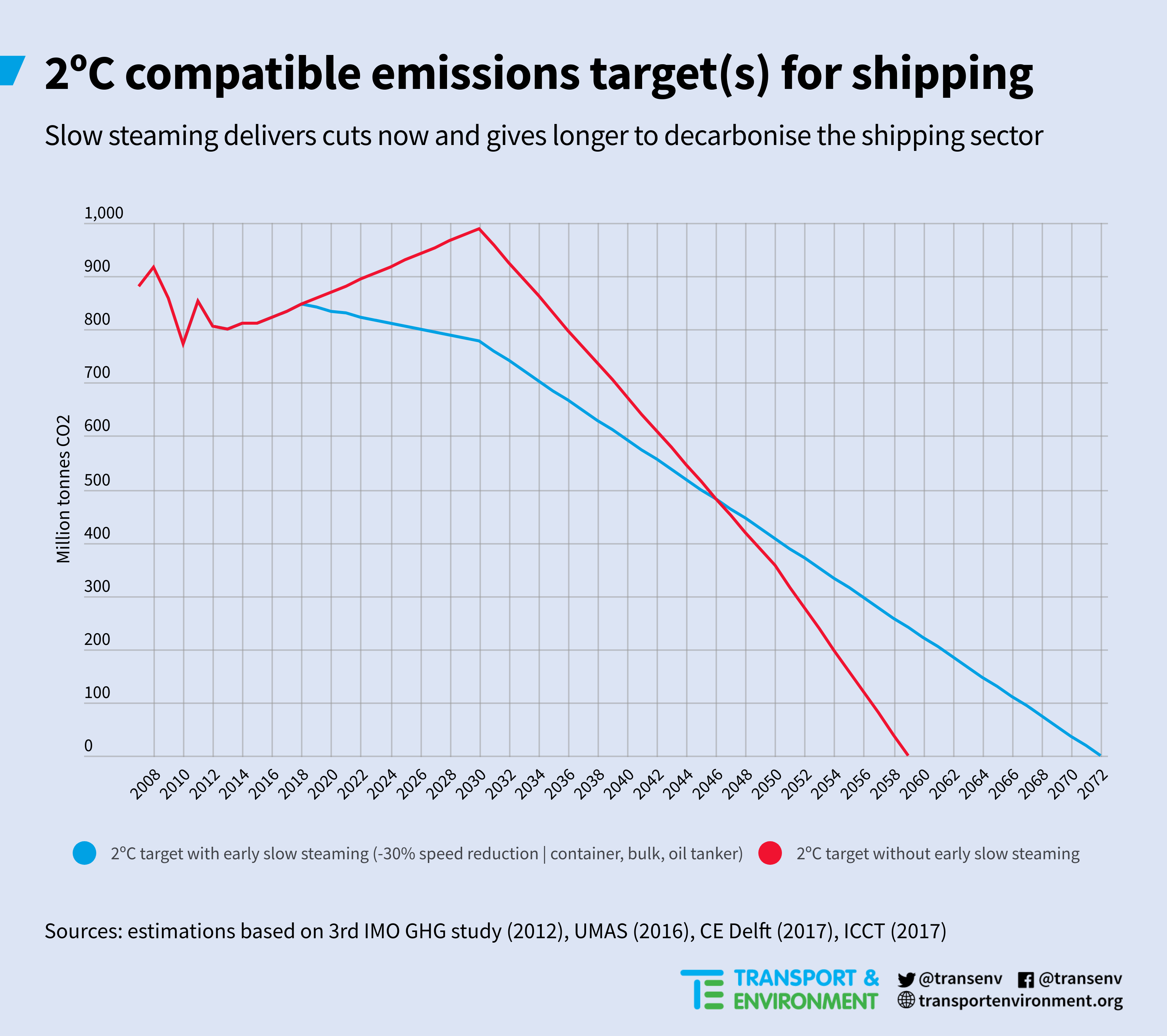

These estimates are based on slow-steaming of containerships, bulk carriers and tankers alone – cumulatively responsible for around 50% of the sector’s climate impact. This means that slow-steaming the rest of the global fleet will extend the “grace time” for decarbonisation even further, possibly into the early 2040s (for 2ºC target, the benefits of slow steaming would be much bigger – see graph 2:

Secondly, without early action the sector would have to switch to zero-carbon technologies almost overnight in 2030 if 1.5ºC is to be averted (see the dark steep blue line in the graph). Even if it were technically and logistically possible, this would likely lead to sizeable disruptions in the operation of the sector, and could even disrupt global trade. Early slow-steaming, in this regard, would make the transition smoother, making the process of decarbonisation less disruptive. It is a bit like starting to revise for an exam several weeks beforehand, as opposed to leaving everything to the night before. We all know what that means for the results.

Fantastic work is being done to bring forward the “Tesla-moment” for shipping, when disruptive innovations in battery storage, hydrogen fuel-cells, ammonia, wind and solar free the industry from its reliance on fossil fuels. Longer term, such a transition is inevitable.

But we can no longer sit back and wait for silver-bullet technologies to come and save us. We need action, and we need it now. This April the world is meeting in London at the UN’s International Maritime Organisation to try and forge a carbon reduction plan for shipping. The shipping industry must know that the world is watching and expects an ambitious, binding deal to reduce its carbon emissions starting immediately.

Otherwise, a warmer world awaits, with even more storms, floods and extreme weather events than we had in 2017.