Interested in this kind of news?

Receive them directly in your inbox. Delivered once a week.

Electrification as part of freight logistics could contribute to reducing land freight emissions by 2050 by an additional 27%, which in combination with the low-hanging fruit (dotted line below) discussed in previous snippets, could bring emissions down by 63% compared to a business-as-usual scenario. By 2050, not even the whole potential would be unleashed as the fleets would need longer to fully renew to achieve its maximum emissions saving potential. To calculate it, T&E used its new European Union Transport Roadmap Model (EUTRM) tool.

Full decarbonisation requires a shift to new technologies and energy carriers. To reach zero GHG emissions by 2050, renewable, decarbonised electricity is fundamental. Currently, battery electric vehicle technology is limited to small and medium trucks with short, urban mission profiles. Given the rapidly falling battery costs, predictable routes and easy overnight recharging, delivery trucks and urban buses can, and should, become fully electric. In our study we assumed that 60% of all new small trucks sold in 2050 could be electric. Another input was all new urban buses being fully electric by the same year.

Regarding larger trucks, e-highways could power long distance trucks with renewable electricity while they drive. The Siemens e-highway concept connects a hybrid electric truck with overhead lines through a pantograph (like a tram). This trolley truck concept is being tested in Sweden, Germany and California in cooperation with Volvo and Scania. Other electric highway options are also being developed, including in road conductive tracks. The technology which eventually wins however, would not change our underlying assumptions. By 2050, 40-60% of highway trucks could be e-highway trucks. The advantage of the e-highway system is its high efficiency, its flexibility, and the comparatively lower vehicle and infrastructure cost – since only a small part (initially the core) of the road network needs to be ‘electrified’. According to the German environment agency it is by far the most cost effective route towards zero/low emission trucking. We assumed that the first catenary trucks will find their way into the market from 2025. By 2050, 90% of all new long-haul registrations would be catenary trucks, and the relative share of electricity used by these hybrid trucks would also increase over time as battery technology improves.

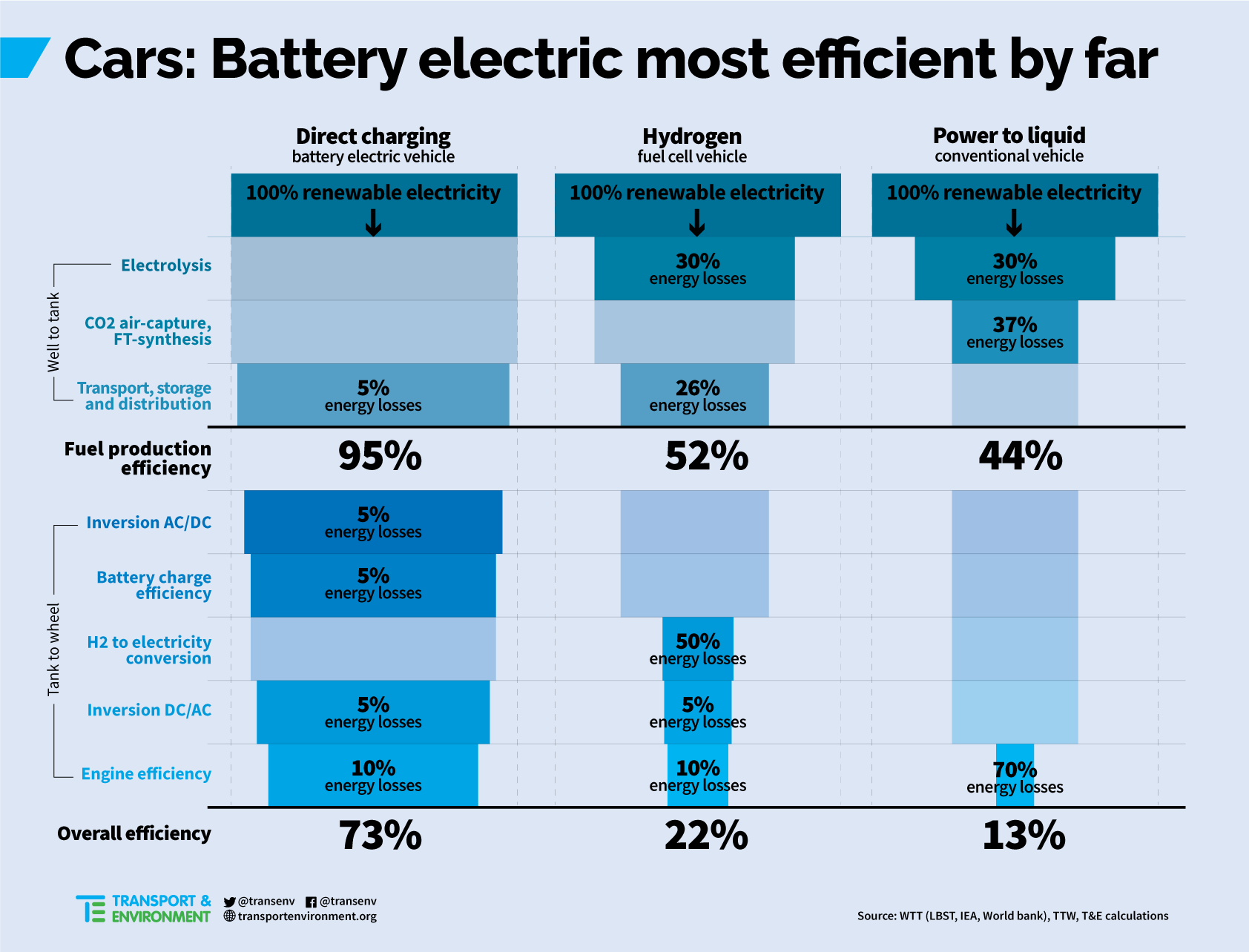

Another argument to use as much direct electricity as possible is that it is significantly more efficient: by definition, less primary energy is needed than for other zero-carbon alternatives (see graph below). More details about hydrogen and power-to-liquid will be included in an upcoming snippet.

In order to unlock all this potential, a zero emission vehicle (ZEV) mandate/quota for buses and delivery trucks would be a first step in the right direction. The Commission is considering a ZEV mandate for urban buses, which should also include all delivery trucks. This should be complemented by zero-emission freight strategies for cities across Europe.

Building the right infrastructure is another key condition. Battery electric or e-highway trucks require infrastructure to operate. Based on current knowledge, battery charging in cities and e-highway infrastructure on highways appear to be the most promising investments. The EU should use its post-2020 transport budget lines to co-finance such projects and avoid spending on technologies which do not have the potential to decarbonise, like natural gas.

Road tolls could also play an important role in freight decarbonisation, because on the one hand the revenues could be used to develop the infrastructure, and on the other the proposed 75% discount on road tolls for zero emissions vehicles by the Commission as part of the Eurovignette review could also become a driver for these technologies.

For more details, have a look at section 3.2, 3.2.1 and 3.2.3 of our new study.