The European Commission’s Effort Sharing Regulation – the framework that sets national emissions reduction targets – contains the rules for assessing and controlling member states’ compliance with their targets. But these rules lack the stringency that deter countries from deviating from their targets, meaning that countries are left off the hook when not meeting their reduction targets.

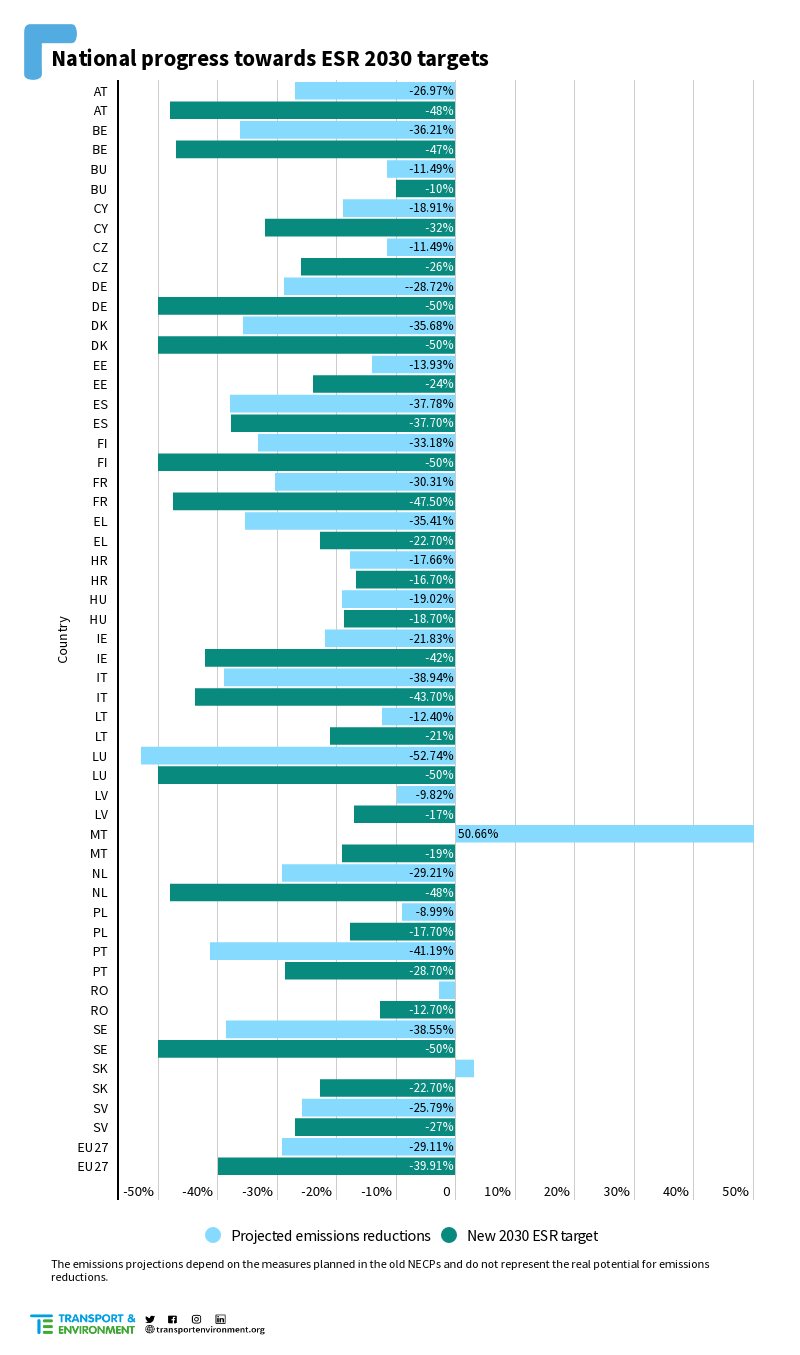

The Effort Sharing Regulation is the EU’s framework that sets climate targets for the period 2021-2030. As part of its Fit for 55 package, the Commission in July proposed to increase the target for the ESR sectors from -29% to -40% (compared to 2005).

A new evaluation by T&E and Climate Action Network (CAN) Europe found that the current compliance framework under the ESR is weak. The ESR provides two processes for ensuring countries respect their emissions limits.

In the first one, the Commission assesses progress towards the ESR targets and can impose corrective actions from member states if they are not making sufficient progress. This corrective process, however, lacks teeth:

- There is no guarantee that member states will present good corrective plans if found out of track;

- If a country breaches its annual emission limit, no penalty is provided, not even if it does so for two consecutive years;

- The process is not transparent, meaning national civil societies lack the data to keep their national governments accountable.

The second process is a compliance check every five years, which is also flawed in its design. The automatic sanctions that are currently provided are not tangible, immediate nor credible. If the EU is to meet its climate goals, binding national climate targets require strong compliance rules. These could include:

- A financial sanction to penalize non-compliance;

- A ban on the use of all flexibilities as long as non-compliance persists;

- The right of national civil society to bring their government to court if they don’t comply with the ESR;

- A formal explanation by the Member State as to why it has not met its target;

- Mandatory and transparent scrutiny of the corrective action plans by the Commission;

- Public disclosure of corrective action plans, allowing NGOs and individuals to scrutinize the methods used.

If binding national targets are not supported by a strong compliance framework they become mere suggestions. Any risk of national non-compliance in 2030 – which would have disastrous effects on the climate – should be prevented.

Without a strong compliance framework, member states won’t put in place the necessary measures to fulfill their climate obligations. This would result in insufficient emissions reductions. For a country like Germany, no new measures would result in a mere 29% emissions reduction for the ESR sectors. With a more ambitious climate plan, the country could reduce up to 50% of emissions in those sectors.