Originally published in Euractiv

Imagine that your house is on fire, and you call the fire brigade. The person on the other end of the phone takes note and promises to put it out next week.

This is exactly the approach that Europe has adopted in setting decarbonisation goals for international shipping.

This summer, the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) will finalise the revision of its so-called Initial Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Strategy, setting decarbonisation targets for international shipping.

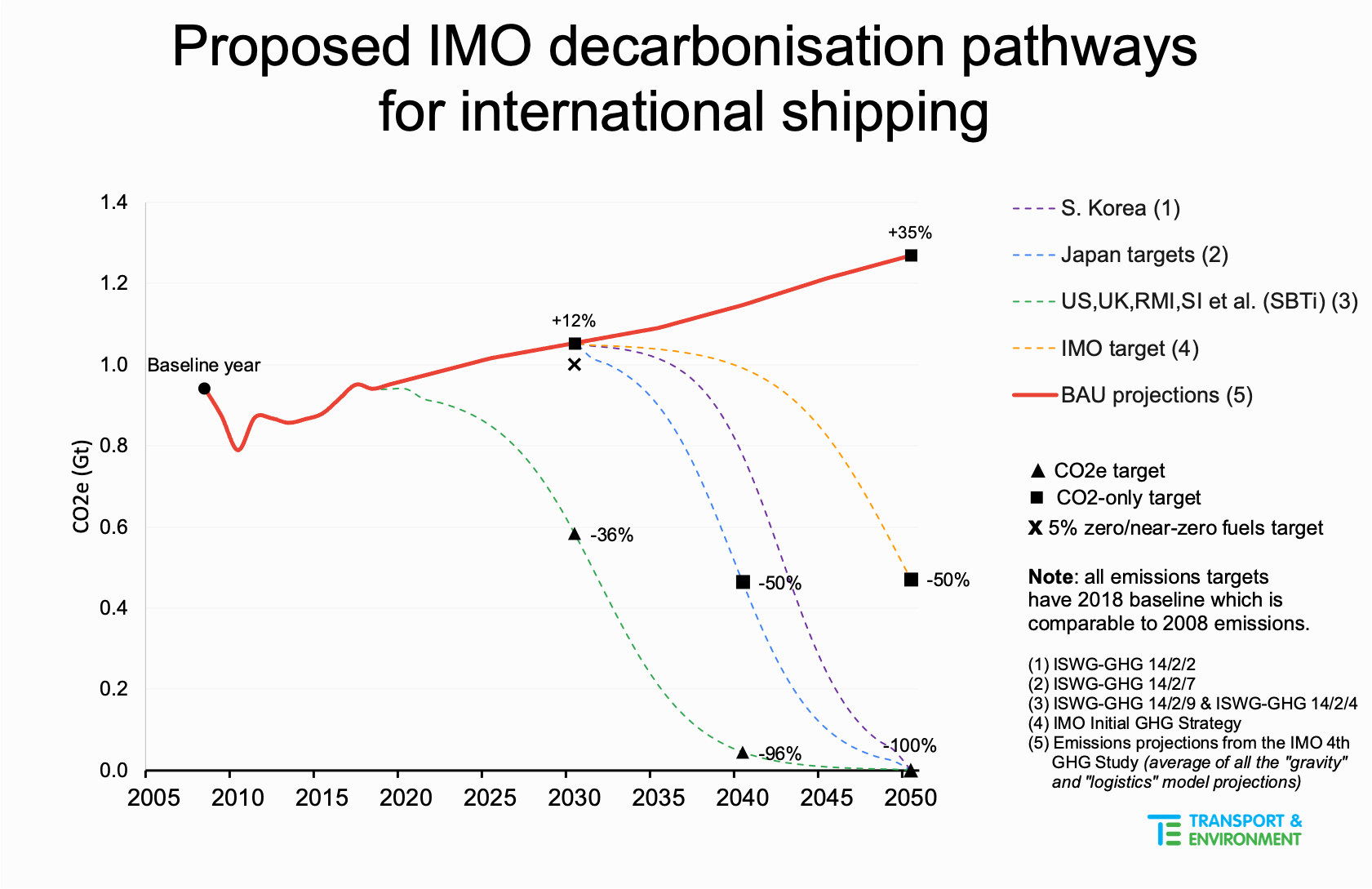

Under current policies, the organisation predicts up to 50% growth in shipping emissions.

In this state of perpetual global climate despair, the EU would be expected to act like the climate leader it has long claimed to be. But the reality could not be more different.

While the EU has committed to reaching zero emissions by 2050, it has refused to express support for any intermediate targets, which are key to remaining in line with the Paris Agreement.

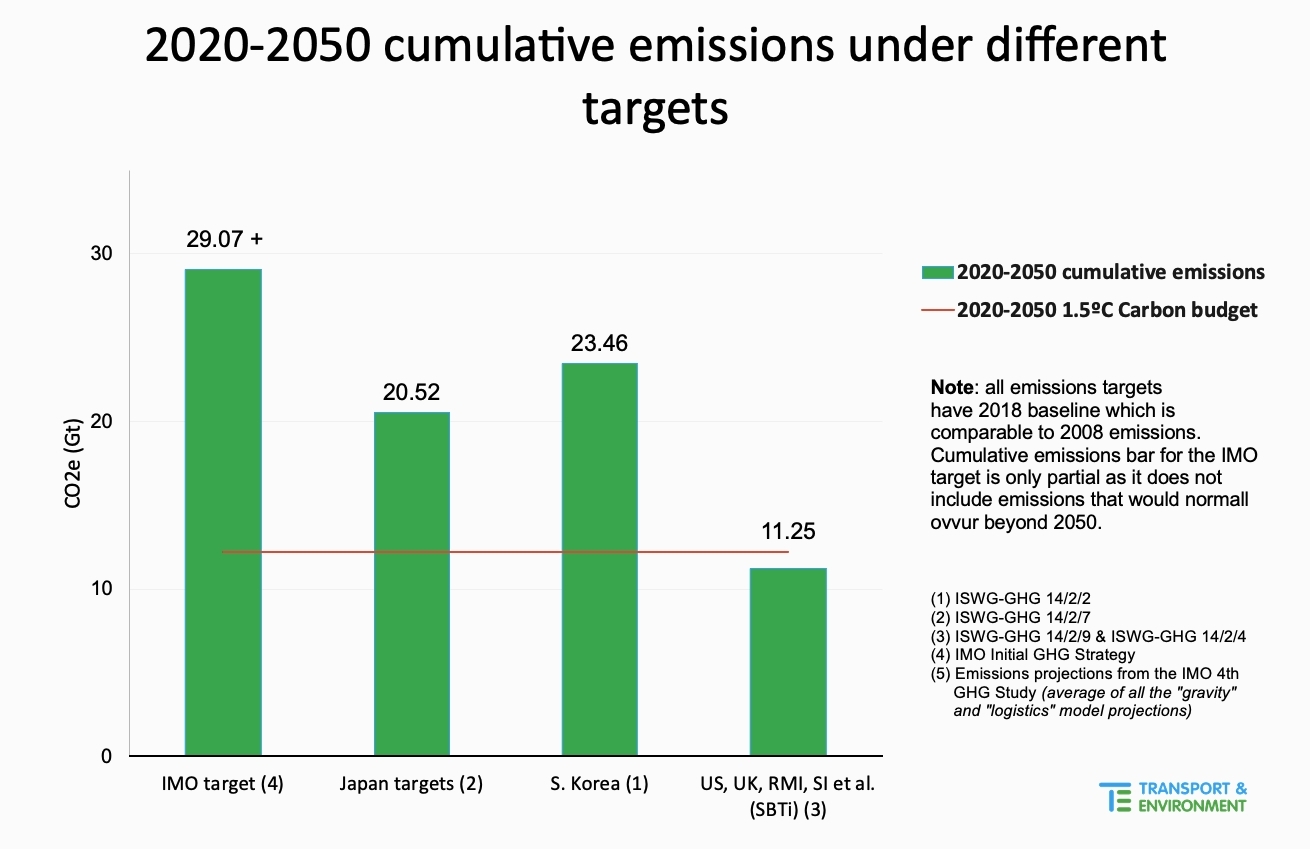

The science is clear on this: targets must not overshoot the carbon budget, the maximum amount of emissions permitted over a certain period of time beyond which achieving the 1.5°C temperature goal becomes impossible.

Think of it like a bathtub that’s been filled. If you keep adding water, at some point, it will overflow. Eventually, turning the tap off will not fix the damage that has been done.

This means that under the carbon budgets approach, the cumulative annual emissions between today and 2050 matter more than the final decarbonisation date alone.

Shipping emits about 3% of man-made emissions. Under what is known as the “fair-share” approach, the industry should not emit more than 12.2 gigatonnes (GT) of GHG starting from 2020, which equals 3% of the global carbon budget to achieve the 1.5ºC temperature goal.

Countries like South Korea and Japan have both committed to reaching zero-by-2050, but the sum of their projected emissions under the proposed targets overshoots the carbon budget by 11.45 and 8.5 GT CO2e, respectively.

This is equivalent to France’s total emissions over 20 and 30 years. Both countries are against setting absolute emissions targets for 2030, while South Korea also argues against setting any 2040 target at this stage.

Fortunately, the US, UK, Canada and many Pacific island countries propose “science-based targets” (SBTi).

With 37% emissions reduction by 2030 and a nearly total emission reduction by 2040 (96%), the SBTi lead to only 11.25 GT CO2e cumulative emissions by 2050. This is the only trajectory where cumulative emissions by 2050 remain within the 1.5ºC carbon budget.

But Europe has not yet endorsed SBTi, and there are several reasons for this. Any substantial short-term GHG cuts inevitably require either trade demand reduction or ship speed reduction, neither of which is appealing to the European transport ministries.

A 10% reduction in vessel speed leads to about 30% emissions savings, but potential loss of profits is still a much bigger concern for companies than the disastrous effects of global warming.

Also, while committing to long term goals is easier for politicians who will long be retired in 2050, setting a near-term target potentially puts their re-election at risk.

Not to mention the vested interests that influence key political decisions, whether it is the transport directorate of the EU Commission that advises EU member states (whose head was forced to resign due to ongoing corruption investigations) or powerful players like France where ‘revolving doors’ between the government and shipping industry have been in the media spotlight for some time now (e.g. Djebbari-gate or Kohler-gate).

Either way, the EU refusing to support ambitious climate targets for 2030 and 2040 means implicitly endorsing uncontrolled emissions growth for the next two decades, a position currently defended by climate laggards like Russia, China and India.

And if you think Europe is simply trying to ‘safeguard’ its economy, think again.

A recent study estimated that for every year of inaction, the shipping industry will have to shell out between $1.8 billion to $7.1 billion by 2050 and up to $25 billion/year by 2100 to deal with the adverse effects of climate change on the industry such as re-routing, increased damage to port infrastructure, lower port productivity, and decreased demand for services.

Countless citizens and businesses will soon bear the consequences of the EU’s unwillingness to put out a fire already burning the continent’s future.

But Europe can still rectify this if it stops burying its head in the sand and endorses 2030 and 2040 science-based targets pleaded for by so many.