Reactions to the Glasgow COP were mixed. Boris Johnson called it game changing. Some talked about “catastrophic betrayal”. Greta Thunberg called it a failure and a PR event. Or more succinctly: blabla. Which was it?

COP isn’t just about what happens at the conference. It is also what happens in the run up to it. For example, the government in my native Flanders in Belgium hammered out a climate plan which included mandatory energy renovation of homes and 100% emissions free car sales by 2029. All this in under a week so the environment minister wouldn’t have to travel to Glasgow empty handed.

Neither is any COP likely to be the world’s ‘final chance’ to stop global warming. Measured against that ambition every COP will be a failure. This is concerning because it drives people to doomism and undermines their faith in democratic or consensus-made decision making.

COP26 itself saw some progress with delegates reaching a deal on the infamous Article 6 clause of the Paris treaty, unlocking long-stalled negotiations on how to avoid double counting from carbon offsets. As explained in this Öko Institute blog, this sadly doesn’t mean offsets have now become a credible solution.

COP’s main outcome though was a flurry of commitments: a plan to end overseas coal financing; a global coalition pledging an end of combustion engine cars sales; and a headline-grabbing pact by countries accounting for 85% of global forests to completely end deforestation by 2030.

It is easy to say all of this is just PR and ‘blabla’. Evidently only policies and laws guarantee results. But lofty goals can create space for new policies.

The good news is that the EU is about to release a law to cut back on ‘imported deforestation’. A draft of the law includes cattle, soy, palm oil, coffee, cacao, timber and leather (a big problem, see this New York Times investigation). Companies selling those products would have to prove they did not source from recently deforested areas. Although the plan omits key raw materials for car production such as rubber, it is progress.

Sustainable sourcing has clear limitations, though. As long as demand for high deforestation risk commodities like palm and soy grows, pressure on rainforests, savannahs and peatlands increases. One key way to reduce this pressure is to cut down unnecessary consumption of valuable products like rapeseed, palm and soybean oil.

The obvious place to start would be biofuels. More than a million hectares of land previously occupied by rainforest, peatlands or other natural habitats is now devoted to growing palm for European biodiesel. Millions more are used to grow rapeseed and soy to burn in our cars and trucks. This was always hard to defend, but in light of the recent deforestation deal it has become untenable.

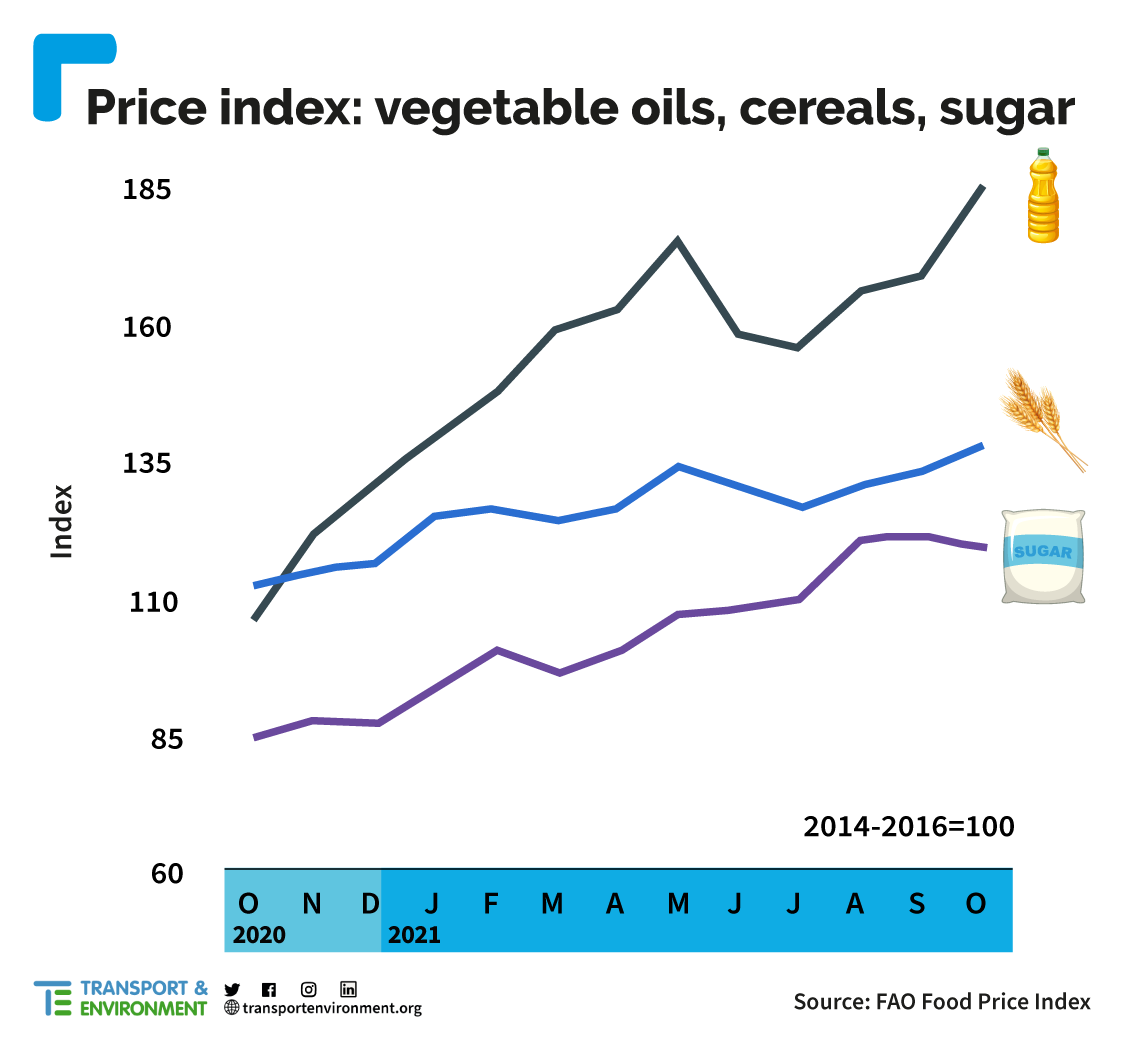

There’s more. Global food prices are hitting levels not seen since hunger and anger led to a wave of revolts in the Arab world back in 2010-11. Vegetable oil prices in particular are out of control. Government mandates to burn rapeseed, soy and palm oil add fuel to the fire of inflation and supply chain disruption. European consumers pay the price, both at breakfast and at the pump.

Some businesses are starting to understand this isn’t just some esoteric disagreement between environmentalists and biofuel producers. In the US the American Bakers Association is mobilising against Biden’s plan to increase soy biodiesel blending because it pushes up food prices. Even before the -55% climate goal was adopted EU countries were planning to increase biofuel burning. This could put unprecedented pressure on food and energy prices. On the other hand, if Europe were to move away from biofuels it would send a signal to the world that decarbonisation can be done without biofuels and immediately alleviate pressure on the world’s forests.

All of these are decisions that can and must be taken at EU and national level. COPs and global agreements are ideally suited for developing a globally shared sense of purpose. That’s what the commitments are for. But we need laws and policies to deliver progress in the real world. This is as true for switching to 100% emissions free cars as it is for ending deforestation caused by European biofuels.