What follows is a summary of T&E’s report on a European response to the Inflation Reduction Act. The full report can be downloaded on this page.

The European Green Deal is one of the world’s most ambitious climate policies to usher the European Union into the net zero economy by 2050. To happen, it will require a massive ramp up of technologies from wind turbines to electric car batteries, but the question is how much of the value will be captured by industry in Europe.

The global race to lead the production of these cleantech, as well as raw materials that go into them, has been unfolding for a few years now. Europe has secured much commitment and investment in the area of electric cars (EV) and batteries already. Dozens of billions have poured into scaling EV manufacturing and batteries. Over half of all lithium-ion batteries on the EU market in 2022 were produced in Europe, with the continent projected to become the world’s second biggest battery cell manufacturer by the end of the decade.

But the US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), launched in August 2022, has changed the rules of the industrial game and might make companies re-prioritise the current announcements in Europe towards the US. For EVs and batteries, the risk is that the projects – and therefore Europe’s ambition – gets delayed. For critical metals and their processing, where Europe is only starting to catch up, the risk is that investments would simply go elsewhere. In just a few months since the launch of the US IRA, investments into battery factories, new mines and electric vehicles have mushroomed in North America. This is in response to the requirement that 40% of battery metals need to come from the US and half of all battery components made in North America from 2024 for the full EV tax credit to apply. The battery supply chain of an electric car will receive up to USD 50 of subsidy per each kWh of battery, or over a third of the total battery costs today.

So far Europe has one of the most ambitious climate regulations in the world. The next step now is to beef it up with a robust industrial muscle to ensure we capture parts of the growing value chain for our jobs and economic resilience.

What should be Europe’s response to the US IRA’s provisions on electric vehicle supply chains?

The concern with the US IRA is not the electric car (EV) tax credits, since the EU is not expected to export large numbers of electric cars in the foreseeable future (if that changes – higher EV trade tariffs shall be introduced). Instead, the real risk is the long-term and bankable production tax credits, worth hundreds of billions of dollars, given to batteries and the critical metals supply chain until 2032. As the capital requirements to ramp up cleantech at the speed and scale required are enormous, Europe should look at its own funding to make production attractive.

Europe already spends a lot of money to support the sales of EVs and the supply chains, including vehicle manufacturing, battery production and upstream processing. At the EU level, more than EUR 20 billion has been devoted to the battery value chain via the IPCEI framework, the EIB and research funding in the last few years. Dozens of billions more are available via the InvestEU and the EU Recovery and Resilience Facility launched in the aftermath of the Covid pandemic, mostly disbursed at the national level. Almost EUR 6 billion was spent in 2022 alone to subsidise the sales of electric cars across the member states.

Even if not in the hundreds of billions, these sums are nonetheless substantial. The problem is not only the lack of money, but the complexity in getting it: the approval processes are often slow (with deadlines unknown), bureaucratic and not bankable in the same way as the US IRA production credits are. E.g. the EU state aid rules (under which most national funding falls) ask companies to prove their projects would not have been possible without such funding. In addition, many funding programmes are annual and lack the long-term certainty needed. What is needed is to streamline the state aid rules, focusing on production aid, for the electric vehicles, renewables and raw materials businesses directly affected by the US IRA. Europe should introduce a green simplification agenda so building a battery plant does not take the same amount of time as a coal plant.

However, simplifying state aid is not enough as it would only benefit deep pocket member states such as Germany, but leave many other countries behind. This is a big problem. First, cash rich countries might not be where the best potential for metals processing or renewables is as it depends on geology, natural resources and innovative ideas. Crucially, this is about the European level playing field to make sure Europe as a whole meets its industrial and climate ambitions, not one or two of its member states.

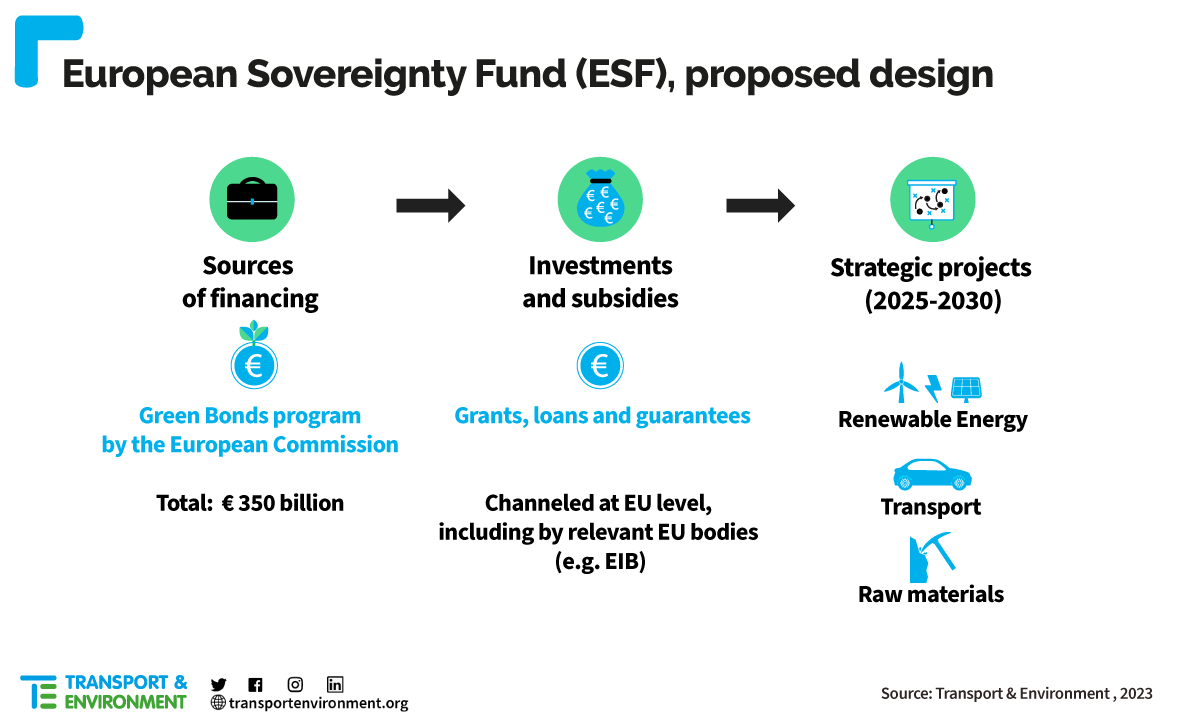

That’s why to accelerate the development of truly European green industrial policy, the European Sovereignty Fund (ESF) should be established as a matter of urgency and equipped with financial firepower in the scale of at least EUR 350 billion via joint debt issuance from the European Commission. The ESF should focus on scaling excellence in renewable energy (not fossil fuels!), electromobility and green battery supply chains, i.e. target the sectors directly affected by the US IRA.

Ultimately, the ESF should become the backbone of EU’s green industrial policy. There are clear benefits of joint borrowing from the standpoint of European governments. Given the different debt capacity of EU Member States, joint borrowing allows for the states in a more precarious financial situation to still access financial markets, so ensure best projects (rather than those in richer regions only) happen. Joint borrowing also provides better terms and conditions than what governments would be able to access on their own. Europe can’t compete with the likes of the US or China without a strong EU financial arm to back our industrial and climate ambition.

European potential in batteries and critical metals

Some in Europe, including President Macron and EU Industry Commissioner Breton would like to see similar “made in Europe” provisions. While outright local content requirements might be difficult, there is significant potential in the EV, battery and critical metals supply chain that Europe can and should capture via strong industrial policy:

- Europe is on track to produce 6.7 million battery electric cars (BEV) by 2030, or just over half of all the cars produced, which is in line with the recently agreed -55% CO2 target for carmakers for 2030 that is expected to result in a 50-60% share of BEV sales. This shows that carmakers follow climate regulations and plan domestic investments accordingly. If we accelerate the pre-2030 ambition, notably by setting an EU Fleets mandate for corporate BEV registration by 2026/7, a market for battery electric cars can be a lot bigger in 2027, creating a better business case for the battery value chain.

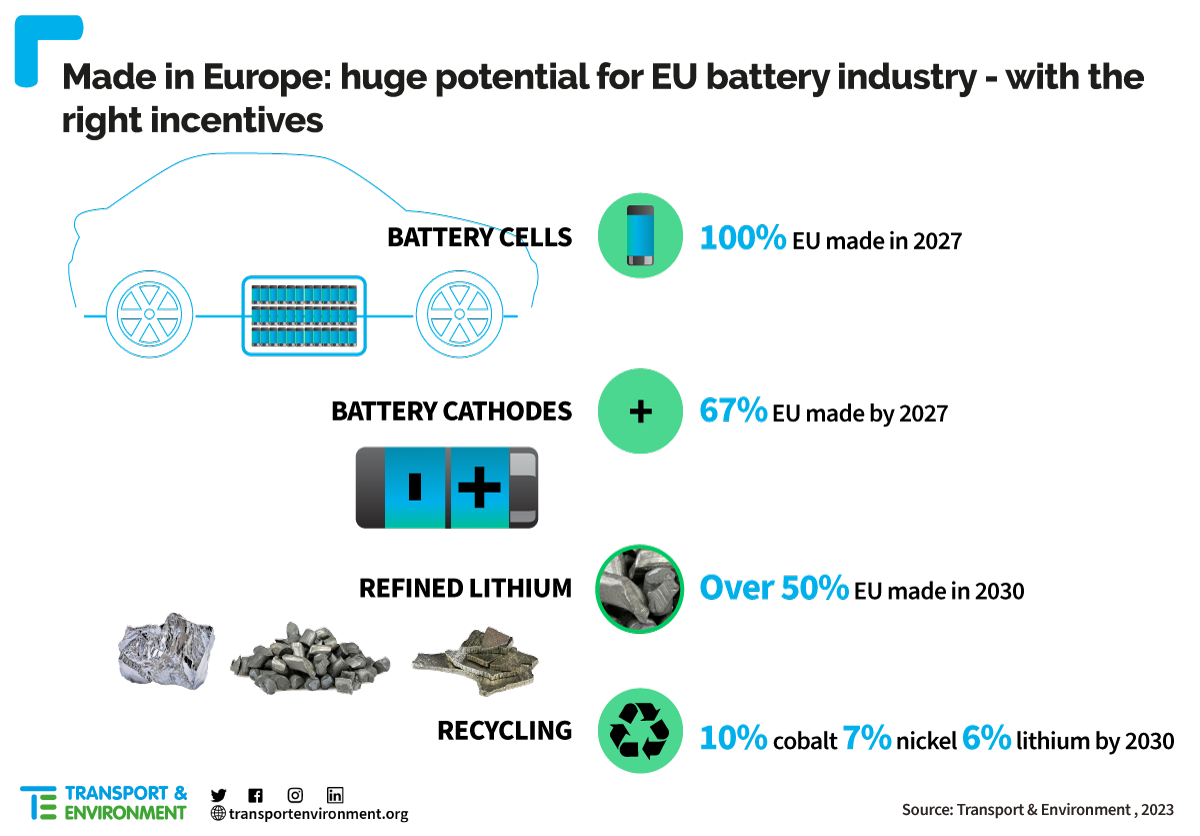

- Half of the Li-ion battery cells used in electric vehicles and energy storage systems in the EU were already made in the bloc in 2022, notably in Poland, Hungary, and to a lesser extent in Germany and Sweden. T&E analysis of the battery cell capacity announcements to date shows that Europe can be self-sufficient in battery cells, i.e. produce 100% of our Li-ion battery cell demand from 2027.

- Looking further into battery components, two-thirds of all the cathode active material (the most valuable part of the battery that contains metals such as cobalt and nickel) can be produced in Europe by 2027 already, with largest projects in Germany, Poland and Sweden. This is where Europe currently leads over the US in terms of project pipeline.

- Investments are also happening in the refining and processing of battery metals, where China dominates today. T&E analysis of the potential to refine lithium shows that over 50% of Europe’s refined lithium demand can come from European projects by 2030. Lithium to feed those can come from global mines, European projects provided these meet high standards (supported by the CRM act e.g.) and – crucially in the future – from battery recycling streams.

- Significant recycling potential also exists: the materials available for recycling from end-of-life batteries or scrap (from European battery factories) could meet at least 8-12% of the critical metals needs in 2030, including a tenth of all cobalt, 7% of nickel and 6% of lithium. Even if the percentages are not huge, these can nonetheless help European companies with shortages or high prices on the spot market (which are set at the margin).

The analysis includes more certain and less mature projects, i.e. shows Europe’s potential which now needs an industrial strategy and smart policy to materialise. Fast tracking best in class green projects, streamlining permitting, as well as targeted funding support, are necessary to capture this value chain in Europe. The Critical Raw Materials act is a key part of the answer here: it should set high-level supply targets by 2030, backed up by a list of “Strategic Projects” (in conformity with high social and environmental standards) that are then fast-tracked across the bloc. Special focus should be on refining & processing, as well as on scaling the European recycling capacity and extracting metals from existing mining waste sites across Europe. Strategic partnerships, especially with Asian and African nations, should underpin the global dimension and help bring higher ESG standards and expertise to the Global South.