Interested in this kind of news?

Receive them directly in your inbox. Delivered once a week.

By declaring the global fleet was way less efficient than it really was when these standards took effect, the IMO stumbled on a plan where in theory it couldn’t lose. Ships would be required to be more energy efficient making the IMO and sector look good. New research released this week illustrates just how flawed the energy efficiency design index (EEDI) is.

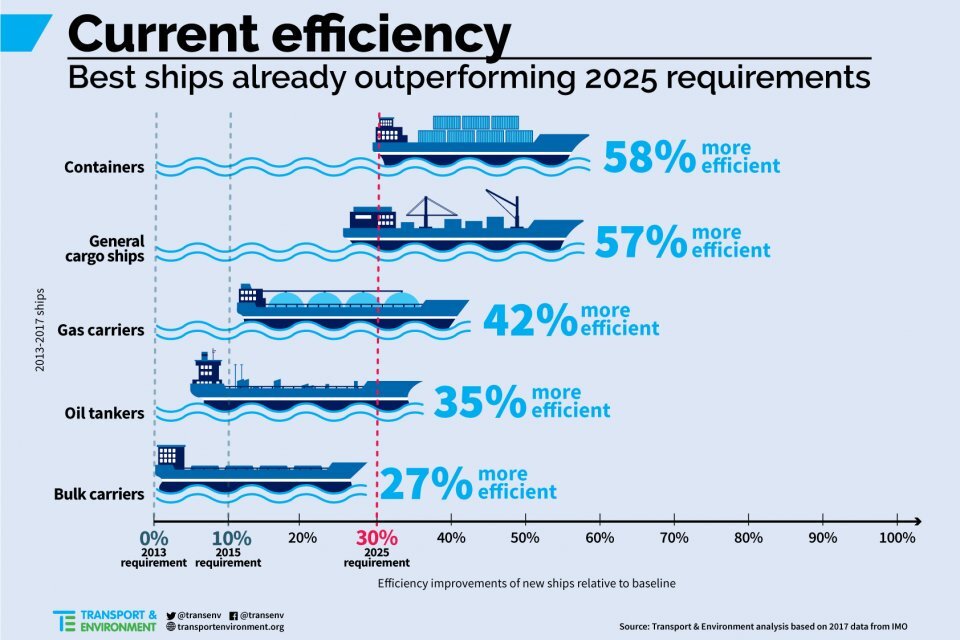

Already almost three-quarters (71%) of all new containerships, which emit around a quarter of global ship CO2 emissions, already comply with the EEDI’s post-2025 requirements. Additionally, the best 10% of new containerships are already almost twice as efficient as the requirement for 2025.

The findings are part of a study based on analysis of the IMO data, and have been released to inform negotiations in a few weeks. It’s important we discuss this now, as the EEDI has long been touted as the first globally binding climate standard – a blue riband policy by the UN and shipping industry alike. Ship owners, represented by the International Chamber of Shipping and BIMCO, have opposed tighter standards as part of efforts to drain all ambition out of IMO discussions on how shipping should decarbonise.

Why is this important?

The shipping sector as whole is one of the fastest growing sources of CO2 and could be responsible for more than 17% of global emissions by 2050 if no action is taken. Despite this, the International Chamber of Shipping (ICS) and BIMCO are claiming that the sector cannot accept any “commitment or intention to place a binding cap on either the international shipping sector’s total CO2 emissions or the CO2 emissions of individual ships”. ICS has argued that a lack of zero/low carbon technologies is the main obstacle. Yet less than 1% of the 2,500 newly built ships analysed in this study reported using even the existing efficiency technologies. So to the question, how can new low/zero technologies be developed if existing ones are not even being used? Why install energy efficiency technologies if they can meet and exceed the design standard without them?

What to do?

The answer is very simple, the EEDI standard is not up for the task if it requires even less from shipowners than what they are doing anyway. Ships built today will still be sailing in 2050 the sector needs to be fully decarbonised, if 1.5C Paris target is to be achieved. If the EEDI is to make any meaningful contribution to shipping’s decarbonisation, it needs to drive innovation, not follow it. The most obvious answer is to tighten EEDI efficiency targets based on the performance of the top most efficient ships in the market. If 10% of the best ships can achieve a higher standard so can the rest of the fleet. Strengthening the EEDI is the lowest of low hanging fruit. If the IMO won’t take timely action on this issue, because of industry opposition, how can it deliver an adequate response to climate change.