Originally published in Trade Winds

War in Ukraine brought into question once again our reliance on fossil fuels to power our economies. Especially oil and gas that fill the coffers of imperialistic regimes ultimately funding tragedies like the one in Ukraine.

The supply of fossil natural gas is an important question in this debate. Europe depends on Russia for more than 40% of its natural gas supplies. It has been traditionally used for heating our homes and producing electricity. But more recently, it is being sold as a solution to “clean up” transportation.

In the wake of the war in Ukraine, Europe is considering how to reduce its reliance on Russian gas. An increasingly loud, but not new, narrative is that we can switch to more liquified natural gas (LNG). As it is in liquid form it is easier to transport by ships and therefore provides more flexibility than gas that passes through pipes. But ships carrying LNG as cargo to help Europe reduce dependence on Russian pipeline gas is one thing, ships starting to use LNG as marine fuel is another. Fossil LNG lobbyists are also eagerly pushing for the latter. This would be a mistake.

For a sector that uses the world’s dirtiest fuels, residual fuel oil, LNG is being promoted as the fuel of the future. While natural gas supplies about 20% of electricity and 37% of heat production in the EU according to Eurostat, it currently makes up only 6% of fuel used by ships in the EU. But that is about to change, as the EU Commission’s proposal for a low greenhouse gas fuel standard (a.k.a. FuelEU Maritime) is designed to increase the share of fossil LNG in shipping. For example, by 2030 EU shipping could be using about 9.3Mt of LNG per year, which is larger than the total annual consumption (8.3Mt in 2020) of a country like Romania. And that leads us to a paradoxical situation given the geopolitical context; why on Earth is the EU pushing shipping towards gas while at the same time it is desperately trying to wean itself off Russian gas?

Natural gas is a fossil fuel and fossil fuel companies want you to believe that LNG is good. While in some cases it can deliver marginal benefits, in most cases it does the opposite because of methane – a potent greenhouse gas – leakage and slippages.

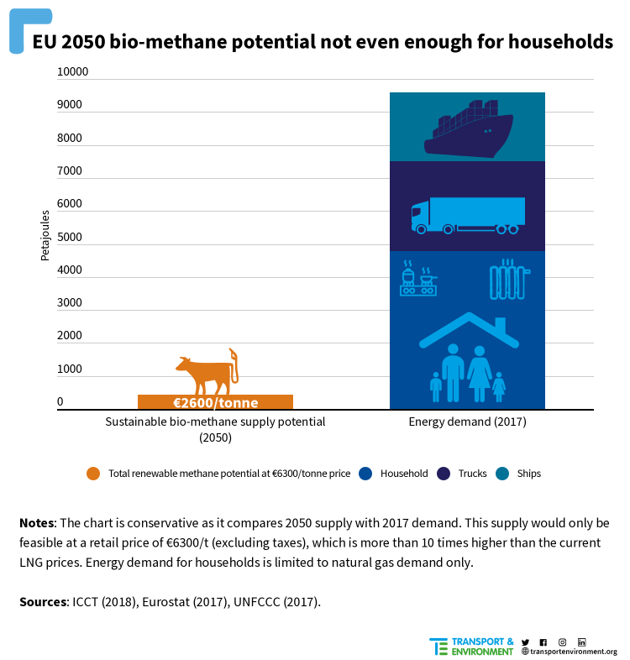

When faced with this argument, promoters of fossil LNG point out the possibility of switching to biomethane – a gaseous biofuel largely derived from waste raw materials. This itself leads to another paradoxical situation: biomethane production is not scalable. There is only so much cow manure and municipal waste to go around.

Analysis shows that biomethane would not be enough to meet the needs of the European households which already rely on natural gas for heating and cooking. In that case, why burn limited resources in shipping that traditionally has not relied on natural gas, while European electricity and heating systems are heavily dependent on Russian gas? Are we not robbing Peter to pay Paul? This just condemns Europe to continued reliance on Russian diktat.

And that is barely scratching the surface. The further one digs the thicker the plot becomes. Russia is not the biggest player in the LNG market, but it is slowly gaining market share. One of its main LNG production facilities is in Yamal peninsula in the Russian Arctic, a project jointly developed by the French oil giant TOTAL.

Surprise, surprise. TOTAL is also one of the most prominent promoters of fossil LNG in shipping and has signed agreements with the French container giant CMA-CGM for supply of LNG and has launched LNG bunkering facilities in the French port of Marseille and Dutch port Rotterdam. To close the loop, CMA-CGM has invested significantly in enormous LNG-powered vessels. Given the geopolitical context, it doesn’t take a lot of effort to realise that switching to LNG in shipping is also feeding the war waging resources of the Kremlin and European fossil companies are equally complicit in that. Let’s not forget, unlike some other majors, French TOTAL decided not to pull out of the Russian oil and gas business.

Zealots for diversification would argue that dependence on Russian LNG can be solved via diversification. But this argument misses the point. Once LNG is in the market, it gets sold and resold making it difficult to trace the origin. For example, despite commitment not to trade shale gas, investigations have revealed that French utility ENGIE has been supplying Europe with high emitting US shale gas.

Secondly, some of the world’s largest LNG importers have not joined Western sanctions on Russia. This means the volumes they were traditionally importing from other sources can be displaced with Russian gas and we are back to square one and Russian gas will keep on flowing.

It is clear that Europe is bound to replace some of the Russian gas with increased LNG imports for the next couple of months. If this is necessary to ensure that houses are heated and lights stay on, it should serve as a wake up call for European politicians not to repeat the mistakes with gas elsewhere. Whether of Russian origin or from elsewhere, natural gas is a fossil fuel. Relying on it puts Europe at the mercy of despots.