Interested in this kind of news?

Receive them directly in your inbox. Delivered once a week.

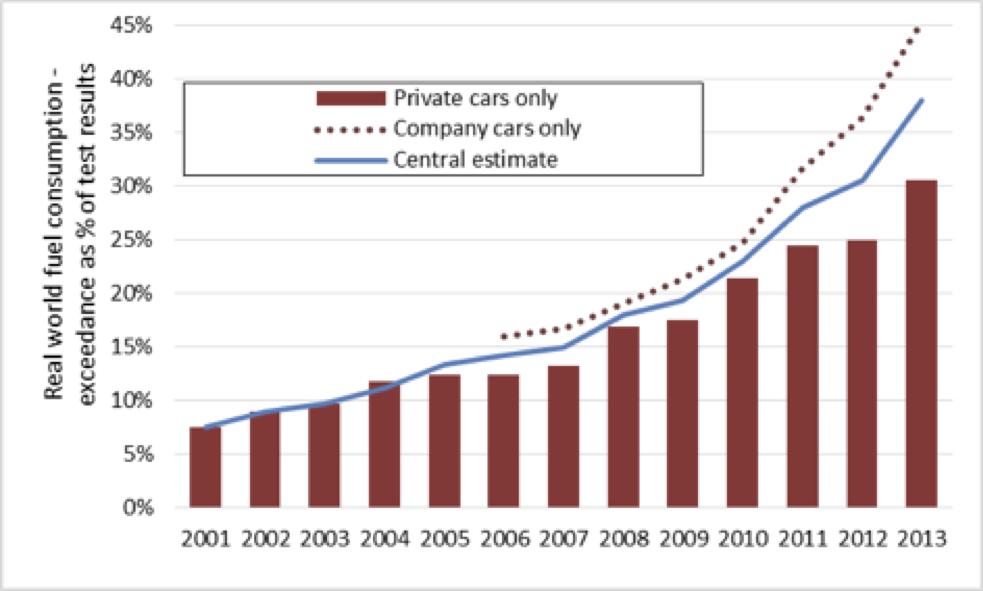

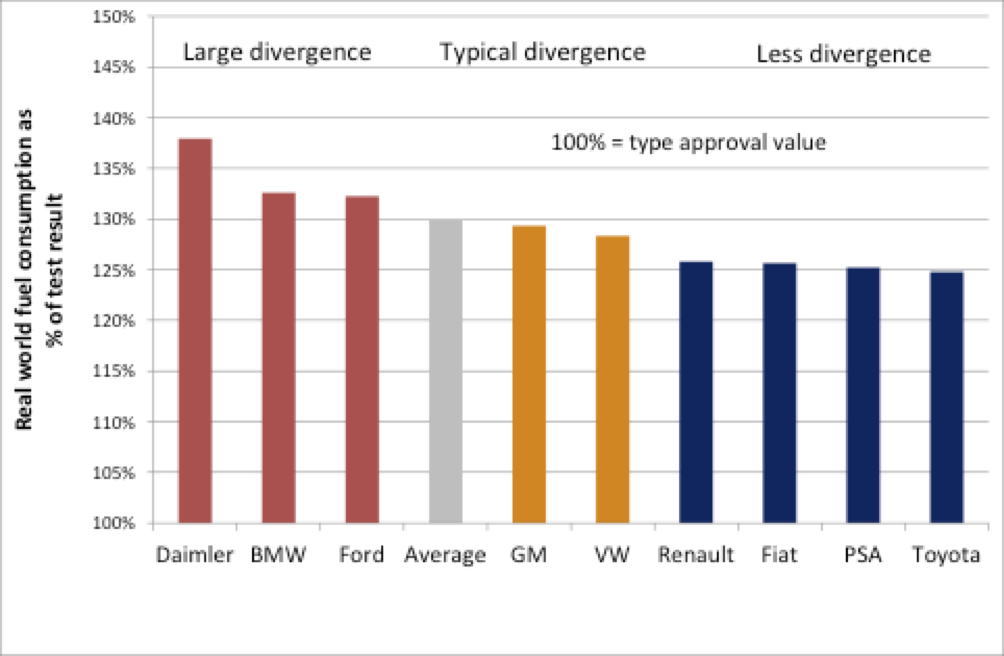

On average, across all car brands, the gap between real-world fuel consumption and carmakers’ claims has widened from 8% in 2001 to a staggering 31% in 2013 for private motorists; the gap for company car drivers averages a whopping 43%. The additional fuel burned compared to official test results costs a typical driver €500 a year.

Half of the official fuel efficiency gains made since EU laws were adopted in 2008 are hot air. For Opel/Vauxhall cars, made by General Motors, less than 20% of the measured improvement in the past five years has actually been delivered on the road.

The obsolete test is unrepresentative of modern cars and driving styles and is full of loopholes that carmakers exploit to produce better test results [1]. Carmakers produce specially prepared prototype vehicles for the test and pay testing services that help to optimise the results. Modern engine management systems are even able to detect when a test is being carried out to deliver better fuel-efficiency results – a technique known as ‘cycle beating’ that was first used to cheat tests for air pollution.

A new, more realistic and robust global test, the WLTP [2], is scheduled to be introduced in 2017, but EU countries are dithering in confirming the date – under pressure from carmakers that want to be able to keep exploiting the loopholes in the current test rules until at least 2022.

Greg Archer, T&E clean vehicles manager, said: “The gap between real-world fuel economy and distorted official test results has become a chasm. The current test has been utterly discredited by carmakers manipulating official test results. Unless Europe introduces the new global test in 2017 as planned, carmakers will continue to cheat laws designed to improve fuel efficiency and emissions reductions. The cost will be borne by drivers who will pay an additional €5,600 for fuel over the lifetime of the car compared to the official test result.”

The growing gap between test and real-world performance is also damaging EU growth and climate goals. T&E forecasts that without the new test the average gap will grow to more than 50% by 2020. The cumulative additional cost of fuel that motorists will be required to buy as a result of test manipulation will amount to nearly a trillion euros in 2030. This is oil the EU must import, much of it from Russia, damaging balance of payments and lowering growth as money flows out of the EU economy. The cumulative additional CO₂ emissions are estimated to be about 1.5 billion tonnes, increasing the risk of dangerous climate change.

US authorities have been far more effective in identifying carmakers unfairly distorting tests. Hyundai and Ford have been required to reimburse customers for incorrect fuel economy figures while Mercedes and BMW-Mini have also been recently caught and are awaiting sanctions to be imposed. Checks on production cars by the independent US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) have identified the anomalies, unlike the totally ineffective system in Europe.

“The US has shown how to provide accurate consumer information and limit the abuse of official tests by carmakers through effective market surveillance by an independent regulator. In contrast, the EU system allows carmakers to pay testing authorities to test prototypes in their own laboratories using an obsolete test. The results are distorted fuel economy figures, more climate-changing emissions and air pollution. If the new European Commission doesn’t strengthen the system of car testing, the only place cars will be less polluting is in the laboratory,” Greg Archer concluded.

Cars are responsible for 15% of Europe’s total CO2 emissions and are the single largest source of emissions in the transport sector. The EU’s first obligatory rules on carbon emissions require car manufacturers to limit their average car to a maximum of 130 grams of CO2 per km by 2015, and 95g by 2021.

Notes to editors:

[1] According to the 2013 edition of Mind the Gap! there are about 20 ways carmakers ‘creatively reinterpret’ test procedures to produce better fuel consumption and CO2 emissions figures (CO2 emissions are directly linked to fuel burned). Among the techniques used are:

- taping over cracks around doors and grilles;

- overinflating the tyres;

- adjusting the wheel alignment and brakes;

- using special super-lubricants;

- minimising the weight of the vehicle;

- testing at altitude, at unrealistically high temperatures and on super-slick test tracks.

[2] Worldwide harmonized Light vehicles Test Procedure