EU ends target for food-based biofuels but will only halt palm-oil support in 2030

EU green energy targets will no longer require countries to subsidise food-based biofuels, after EU governments, the European Parliament and the Commission agreed last month to revise the law. European countries which decide to continue mandate food-based biofuels after 2020 must limit their contribution to the levels achieved nationally in 2020.

Interested in this kind of news?

Receive them directly in your inbox. Delivered once a week.

Under the reforms, the use of the most emitting biofuels, such as palm and soybean oil biofuels, cannot grow above each country’s 2019 consumption levels and should gradually decline from 2023 onwards until reaching a complete phase-out in 2030. However, the deal does allow for these harmful biofuels to still count towards the EU’s green energy targets until 2030. Though the revised Renewable Energy Directive (RED) requires the phasing out of high-emitting biofuels, the Commission still needs to come up with a methodology by February 2019 to make the phase-out operational.

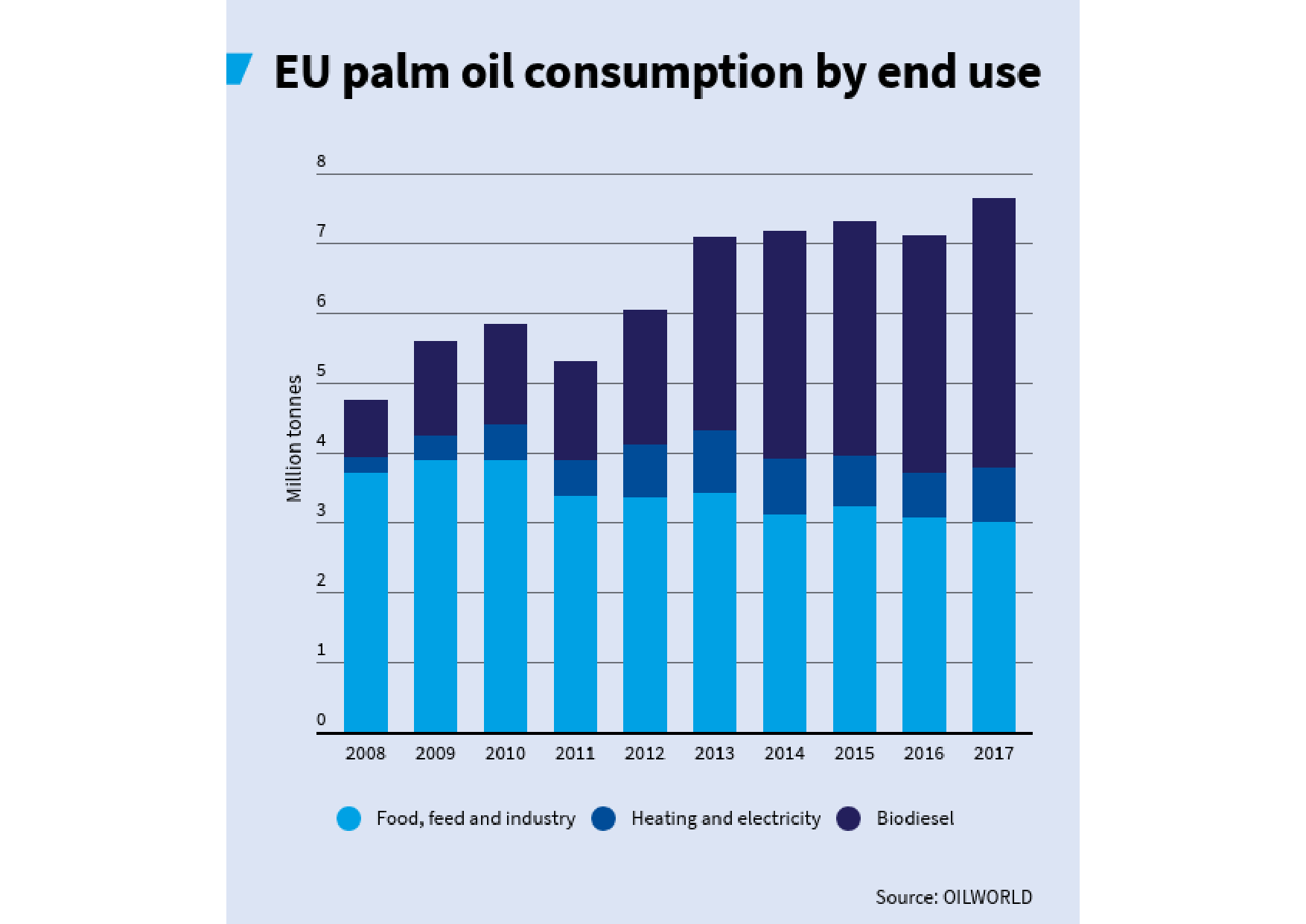

The reforms were agreed days after it emerged that more than half (51%) of all palm oil used in Europe last year was burned by diesel cars and trucks. This 13.5% rise in EU palm oil diesel production over the previous year was recorded by OILWORLD, the industry reference for vegetable oils markets. Since the introduction of the current RED in 2009, palm oil used to make biofuel has steadily increased from 825,000 tonnes in 2008 to 3.9 million tonnes in 2017. The use of palm oil for biodiesel dwarfs palm oil use in other products such as cookies, chocolate spreads, shampoo or lipsticks, which combined add up to 39% of total use in 2017 – the lowest point in the past decade.

Clean fuels manager at T&E, Laura Buffet, said: ‘The EU has removed the single biggest driver for food based biofuel expansion in Europe: the infamous transport target. Governments now have no more excuse to force drivers to burn food or palm oil in their tanks after 2020 and should design policies that promote the use of renewable electricity or biofuels based on wastes and residues.’

The revised RED also sets a de facto target of 7% for advanced fuels. Half of that will need to come from advanced biofuels from waste and residues while the rest is expected to come from renewable electricity and other fuels. In reality the shares of advanced biofuels and renewable electricity will be lower because of multipliers of 2 and 4 respectively.

Laura Buffet concluded: ‘Europeans don’t want to be forced to burn palm oil or food in their cars. It’s a disaster for the climate and biodiversity. It’s a disgrace that Europeans could be burning palm oil for another 12 years and it’s very sad to see the European Commission play such an obstructive role in the final negotiations.

‘Now that the law is signed, the Commission needs to stop playing games and implement the agreement between Parliament and EU governments. That means it needs to deliver a mechanism to phase out palm-oil diesel by the 1st of February 2019 and not a day later.’

The RED was first introduced to accelerate the uptake of renewables such as solar and wind but its transport chapter has promoted the use of food crops like palm oil, rapeseed oil and soy oil to make biofuels. Biodiesel made from virgin vegetable oil is the most popular biofuel in the European market with a market share of three-quarters in 2017. Of all biodiesel, palm oil diesel is the cheapest and has the highest greenhouse gas emissions – three times the emissions of fossil diesel, because palm expansion drives deforestation and peatland drainage in Southeast Asia, Latin America and Africa.

Biofuels can be counted as zero emissions energy for climate accounting purposes. If we would properly account for biofuels’ overall emissions, road transport emissions would be 10% higher.